Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

- The Collection

- The American Wing Ancient Near Eastern Art Arms and Armor The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing Asian Art The Cloisters The Costume Institute Drawings and Prints Egyptian Art European Paintings European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Greek and Roman Art Islamic Art Robert Lehman Collection The Libraries Medieval Art Musical Instruments Photographs Antonio Ratti Textile Center Modern and Contemporary Art

Crop your artwork:

Scan your QR code:

Gratefully built with ACNLPatternTool

The Wine Dark Sea, H

Hew Locke British

Not on view

The Wine Dark Sea , by British-Guyanese artist Hew Locke, is an installation comprised of seven individual sculptures, five of which premiered at his 2016 exhibition at Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art in New York City. The title of the installation is a nod to Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey (both of which use a Greek epithet that serves as the installation’s title) as well as to Derek Walcott’s epic poem Omeros , from 1990, itself a reference to Homer, albeit one that plays out in the Caribbean instead of the Aegean. Crafted from wood, metal, fabric, and found materials, each sculpture in The Wine Dark Sea takes the form of a vessel which is in turn based on a particular prototype. The Wine Dark Sea, U references a Coast Guard skiff. The Wine Dark Sea, AA , takes its inspiration from a more pedestrian sailing boat. The Wine Dark Sea, CC alludes to a stock military boat. The Wine Dark Sea, DD is a model of Sir Francis Drake’s The Revenge, a flagship pitted against the Spanish Armada. (This sculpture evokes more generally the large sailing galleons of the age of discovery and conquest in the 15th through the 18th centuries). The Wine Dark, H is based on a Cuban refugee boat. Boat X (from The Wine Dark Sea, Group 9) is inspired by the boats deployed in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now , the same sorts of vessels employed on military and colonial expeditions around the world. Finally, Boat F (from The Wine Dark Sea, Group 6) typifies the kind of cargo transport used along the Amazon, the site of extractive industries as well as colonial enterprise. Most of the sculptures are embellished with a profusion of chains, plastic flowers, national and organizational coins, medals, imperial regalia, military uniform badges, and the like, all of it rife with historical and symbolic import. A brass plaque on one of the ships alludes directly to a 16th-century German carving of a skeleton, for instance, while another, on The Wine Dark Sea, DD evokes the Queen Mother Pendant Mask , a 16th century ivory mask from Benin, an example of which is in The Met’s collection. The addition of cargo sacks, bags, and clothing suggests the presence of crew members who are otherwise absent. This, in turn, evokes mysterious, perhaps fatal events left to the imagination. Locke’s sculptures are meant to hang from the ceiling, creating a dense, fantastical installation—a kind of suspended flotilla that immerses viewers in both art and history. Like ships themselves, Locke’s procession conjures up a variety of narratives around maritime trade and exchange as well as migration, displacement, slavery, smuggling, colonialism, and military conflict. Locke has referred to sculptures such as these as "votive ships," both "offerings and invocations"[1] inspired by the x-votos he encountered in churches in the Caribbean and beyond. Together and individually, The Wine Dark Sea speaks to the events and catastrophes, many of them involving displaced, disenfranchised peoples of the world, that have taken place on the planet’s many bodies of water. [1] Zoe Lukow, Hew Locke: The Wine Dark Sea [brochure] (New York: Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art, LLC, 2016), p. 3.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

Open Access

As part of the Met's Open Access policy , you can freely copy, modify and distribute this image, even for commercial purposes.

Public domain data for this object can also be accessed using the Met's Open Access API .

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/739594 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/739594 Link copied to clipboard

- Animal Crossing

- Download image

- Enlarge image

Artwork Details

Use your arrow keys to navigate the tabs below, and your tab key to choose an item

Title: The Wine Dark Sea, H

Artist: Hew Locke (British, born 1959)

Medium: Mixed media

Dimensions: 34 1/4 × 32 1/2 × 14 1/2 in. (87 × 82.6 × 36.8 cm) Weight:: 4.9 lb. (2222.625g)

Classification: Sculpture

Credit Line: Purchase, Modern Circle and William Talbott Hillman Foundation Gifts, 2017

Accession Number: 2017.340

Rights and Reproduction: © Hew Locke 2016

Learn more about this artwork

Related artworks.

- All Related Artworks

- By Hew Locke

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Mixed media

- From Europe

- From United Kingdom

- From A.D. 1900–present

The Wine Dark Sea, U

Boat X (from The Wine Dark Sea, Group 9)

The Wine Dark Sea, DD

Boat F (from The Wine Dark Sea, Group 6)

The Wine Dark Sea, AA

Resources for research.

The Met's Libraries and Research Centers provide unparalleled resources for research and welcome an international community of students and scholars.

The Met Collection API is where all makers, creators, researchers, and dreamers can connect to the most up-to-date data and public domain images for The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please complete and submit this form . The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.

Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met

Jump to navigation

Search form

Lapham’s quarterly, a winelike sea.

Homer’s famous “wine-dark sea” has left scholars wondering: how did the Greeks truly see the sea?

By Caroline Alexander

Telemachus and the Nymphs of Calypso , by Angelica Kauffmann, 1782. The Metropolitan Museum of Art , Bequest of Collis P. Huntington, 1900.

The famous likening of the sea to wine has endured through ages, from at least the late eighth century bc , the composition date of the Iliad and the phrase “wine-dark” is now so securely lodged in our collective consciousness as to be known even by people who have never read Homer . It is not the Odyssey , Homer’s sailor’s saga, but the earlier, land-bound Iliad , set on Trojan soil, that first launched one of the best-known of all Homeric epithets on the world. The phrase occurs here only six times, the same incidence as “tumultuous” or “loud-sounding,” while the less vivid “gray-gleaming” is used a dozen times. Yet it is “wine-dark” that has stuck with us, and it is clear why. The phrase is alluring, stirring, and indistinctly evocative. It is also, strictly speaking, incomprehensible, and for all the time the phrase has been relished, readers and scholars have debated what the term actually means. In what way did the sea remind Homer of dark wine? And of the myriad ways to evoke the sea, why compare it to wine at all? A translator’s task is to render into English both the plain meaning and the sensibility—the felt meaning—of a Homeric phrase or word, and so it is a duty, albeit a perilous one, to plunge deeper into this celebrated sea phrase, and grope for clarity. Impertinent questions must be floated: what does it mean—and is there possibly a better rendering?

In ancient Greek, the phrase is oínopa pónton — oínopa being a compound of oínos , meaning “wine,” and óps , meaning “eye” or “face”—literally, “wine-faced,” and thus “wine-ish,” or “winelike.” The enduring “wine-dark” was established in the Greek-English Lexicon famously compiled by Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott and first published in 1843. Liddell, vice chancellor of Oxford University, dean of Christ Church, and one of the most famous Greek scholars of his day, was also the father of Alice Liddell, the muse for Lewis Carroll ’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland . (One imagines the two men busy at their different labors across the quad, the dean seeking to mine and render with exquisite exactitude the innermost meanings of the vocabulary of the ancient Greeks, Carroll plumbing the English language for the inspired nonsense of “Jabberwocky.”) According to Liddell and Scott, oínopa means “wine-colored” and is used by Homer, in both the Iliad and the Odyssey , only of oxen and the sea. When used of the sea, the authors suggest, it is best rendered “wine-dark,” meaning, within its broader context, “the color of dark wine.” They do not hazard what Homer meant by this phrasing, and a survey of principal modern English translations provides neither consensus nor clarity. Richmond Lattimore, in his landmark version of 1951, used, inexplicably, “the wine-blue sea.” Robert Fitzgerald in his translation of 1974 tweaked the dictionary to the collapsed “winedark,” while Robert Fagles stayed true to Liddell and Scott. Other renderings are Stanley Lombardo’s “the sea’s gray wine,” and, most recently, Stephen Mitchell’s “the sea,” in a translation that ditches most epithets and even many simple adjectives.

1:30 a.m. South , by A K Dolven, 2003. © A K Dolven, courtesy the artist and Galerie Anhava, Helsinki.

This wine-dark sea has haunted many imaginations. Nineteenth-century British prime minister William Gladstone posited in Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age that the Greeks had a form of color-blindness, their optical palette limited to black and white, and possibly red. Another theory was that a type of algal bloom, red tide, made the Homeric-era Aegean wine-red. In the 1980s, the view was advanced that since the ancient Greeks mixed their wine with water, the alkaline water common to the Peloponnesus would have turned red wine to blue. Another view came from a retired classicist who watched “an unusually vivid sunset” over the sea at the mouth of the Damariscotta River, in Maine, on an evening when the sky was filled with ash that had floated east from the eruption of Mount St. Helens, and was struck by the color of the sea “reflected in the outgoing tide of the dark estuary.” The sea, he said, was the color of Mavrodaphne, a wine of deep purple-brown hue, and the epithet for Homer’s wine-colored sea, he speculated, meant “sunset-red.” Finally, many contend that the phrase is meaningless, an empty expression with a poetic ring whose purpose is only to fill out the metrical requirements of a line of the verse.

The image Homer hoped to conjure with his winelike sea greatly depended upon what wine meant to his audience. While the Greeks likely knew of white wine, most ancient wine was red, and in the Homeric epics, red wine is the only wine specifically described. Drunk at feasts, poured onto the earth in sacred rituals, or onto the ashes around funeral pyres, Homeric wine is often mélas , “dark,” or even “black,” a term with broad application, used of a brooding spirit, anger, death, ships, blood, night, and the sea. It is also eruthrós , meaning “red” or the tawny-red hue of bronze; and aíthops , “bright,” “gleaming,” a term also used of bronze and of smoke in firelight. While these terms notably have more to do with light, and the play of light, than with color proper, Homeric wine was clearly dark and red and would have appeared especially so when seen in the terracotta containers in which it was transported. “Winelike sea” cannot mean clear seawater, nor the white splash of sea foam, nor the pale color of a clear sea lapping the shallows of a sandy shore.

A fair complexion is unbecoming to a sailor: he ought to be swarthy from the waters of the sea and the rays of the sun.

The Greeks knew the sea intimately, for seafaring was the engine of their culture. As late as 408, Synesius , the bishop of Ptolemais in Libya, invoked his distance from the sea to convey how far he lived from civilization. “Do not think that I am exaggerating,” he wrote, “when I say that people here do not take to the sea, even for the purpose of getting their salt.” He felt, he said, like Odysseus, who, at the end of his wanderings, is sent by an oracle among “men who know not of the sea, nor eat food mixed with salt.” To Xenophon and the army of the Ten Thousand, struggling back from Babylon, the cry “The sea! The sea!” meant they were in reach of home. To live far from the sea was to live in relative isolation, for the sea alone was the highway for ideas as well as commerce. It was also feared—the Greeks, like all seagoing peoples, knew that sea voyages could be perilous. “If ever you turn your misguided heart to trading and wish to escape from debt and joyless hunger, I will show you the measures of the loud-roaring sea,” wrote Hesiod , who is believed to have composed his didactic poem Works and Days a generation after Homer’s Iliad . Only men desperate for wealth, in his view, risk taking to sea; “in their ignorance men do even this, / for wealth means life to poor mortals; but it is fearful to die among the waves.”

The Iliad evokes the sea in dramatic scenes and similes across the range of human experience: men at sea, lonely shorelines, sea storms, waves of men crashing into battle. Its presence is asserted early, in the first book of the Iliad ’s twenty-four, where, although most action takes place within the Achaean camp, evocation of the sea is crucial to some half a dozen scenes. The first mention occurs after an old Trojan priest leaves the Achaean camp, having failed to persuade King Agamemnon to accept ransom for his captured daughter:

And in silence he went along the shore of the tumultuous sea. Then going apart, the old man prayed fervently to lord Apollo.

In response Apollo sends a withering plague to punish the Achaeans for refusing his priest, and Agamemnon finally capitulates, calling for his men to prepare her departure:

“Come let us drag one of our dark ships to the bright salt sea, and assemble in it suitable rowers, and place the sacrifice in it, and embark the girl herself, Chryseis of the lovely cheeks.”

Later, a small band of Achaeans returning from this mission under the leadership of the sailor Odysseus experience the flying joy of sailing a fast boat on a fine day:

They stepped the mast and spread the glistening sails, and the wind blew gusts in the middle of the sail, and around the cutwater the bow wave, shimmering dark, sang loud as the ship proceeded. She swept over the swell, making her course.

When Achilles receives word that he must give up his own captive woman to compensate for Agamemnon’s loss, and loss of face, he reminds his commander, in a blistering speech, that:

“It was not on account of Trojan warriorsI came to wage battle here, since to me they are blameless —never yet have they driven off my cattle, or my horses, nor ever in Phthia whose rough earth breeds warriors have they destroyed my harvest, since there are many things between us, both shadowy mountains and clashing sea.”

H is woman prize confiscated, Achilles calls upon his mother, Thetis, a nymph of the sea, imploring her to seek redress from Zeus; it is at this moment that he stretches forth his hands in imprecation to the “winelike sea.” (The rendering of “winelike” here is based on a new edition of the Greek text of the Iliad , first published in 1998. Instead of oínopa , earlier editions had apeírona , “infinite, boundless” sea, which was followed in almost all previous translations.) Hearing her son, Thetis rises “from the gray salt sea, like mist.” We are still only in book one.

None of these references are gratuitous, nor merely poetic. The sea not only sets the scene of action, but also the mood. A lonely shore is the background for a priest’s prayerful grief, while the tumult of waves mirrors the unrest in his mind. A “bright” sea promises a successful voyage: to men sailing home from a righteous mission, the smiling sea is the friendly, broad road of travel. “Clashing” waves evoke a dangerous distance between Achilles’ homeland and Troy. And the sea’s gray depths are where supernatural beings, forces of nature, abide.

Sightseeing , by Maria Passarotti. 2007. C-print from negative. © Maria Passarotti, courtesy the artist.

The sea’s familiar attributes are also drawn upon in the magnificent word pictures of the Homeric similes to make vivid those scenes and events of which its audience might have had no firsthand experience, such as ranks of warriors on the march:

As when waves of the sea dash on the thundering shore, one after another under power of the West Wind moving— the wave rises first in the open sea, then shattering on land it roars mightily, and curling as it goes breaks around the headland, and spatters foam of the salt sea— so in this way did the ranks of Danaans move one after another ceaselessly to war.

J ust as the English language marks distinct aspects of the sea with distinct terminology, such as sea , ocean , and the deep , so too does Homeric Greek. In the most basic sense, the sea is háls , the same word for “salt,” and is used, according to Liddell and Scott, “generally of shallow water near shore.” The sea as distinct from heaven and land and other water is thálassa , the elemental sea that Achilles evokes to signal the great distance between his home and the Trojans: “Since there are many things between us,/both shadowy mountains and clashing sea.” But the “winelike” sea, the sea that is oínopa , is called pónton —“the open sea,” “deep sea,” “high sea,” the ocean, or what sailors call “blue water.” Indo-European cognates suggest the word’s origin lies in the notion of a “path” or “passage” across the water: “a road where there are obstacles, a crossing,” according to one grammarian. When weeping Achilles looks toward “the winelike sea…stretching forth his hands,” he is reaching for the oínopa pónton , the sea that despite its danger could still provide him passage to the place his thoughts always turn—home.

Homer’s sea, whether háls , thálassa , or póntos , is described as misty, darkly troubled, black-dark, and grayish, as well as bright, deep, clashing, tumultuous, murmuring, and tempestuous—but it is never blue. The Greek word for blue, kuáneos , was not used of the sea until the late sixth or early fifth century bc , in a poem by the lyric poet Simonides—and even here, it is unclear if “blue” is strictly meant, and not, again, “dark”:

the fish straight up from the dark/blue water leapt at the beautiful song

After Simonides, the blueness of kuáneos was increasingly asserted, and by the first century, Pliny the Elder was using the Latin form of the word, cyaneus , to describe the cornflower, whose modern scientific name, Centaurea cyanus , still preserves this lineage. But for Homer kuáneos is “dark,” possibly “glossy-dark” with hints of blue, and is used of Hector’s lustrous hair, Zeus’ eyebrows, and the night.

Ancient Greek words for color in general are notoriously baffling: In the Iliad , “ chlorós fear” grips the armies at the sound of Zeus’ thunder. The word, according to R.J. Cunliffe’s Homeric lexicon, is “an adjective of color of somewhat indeterminate sense” that is “applied to what we call green”—which is not the same as saying it means “green.” It is also applied “to what we call yellow,” such as honey or sand. The pale green, perhaps, of vulnerable shoots struggling out of soil, the sickly green of men gripped with fear?

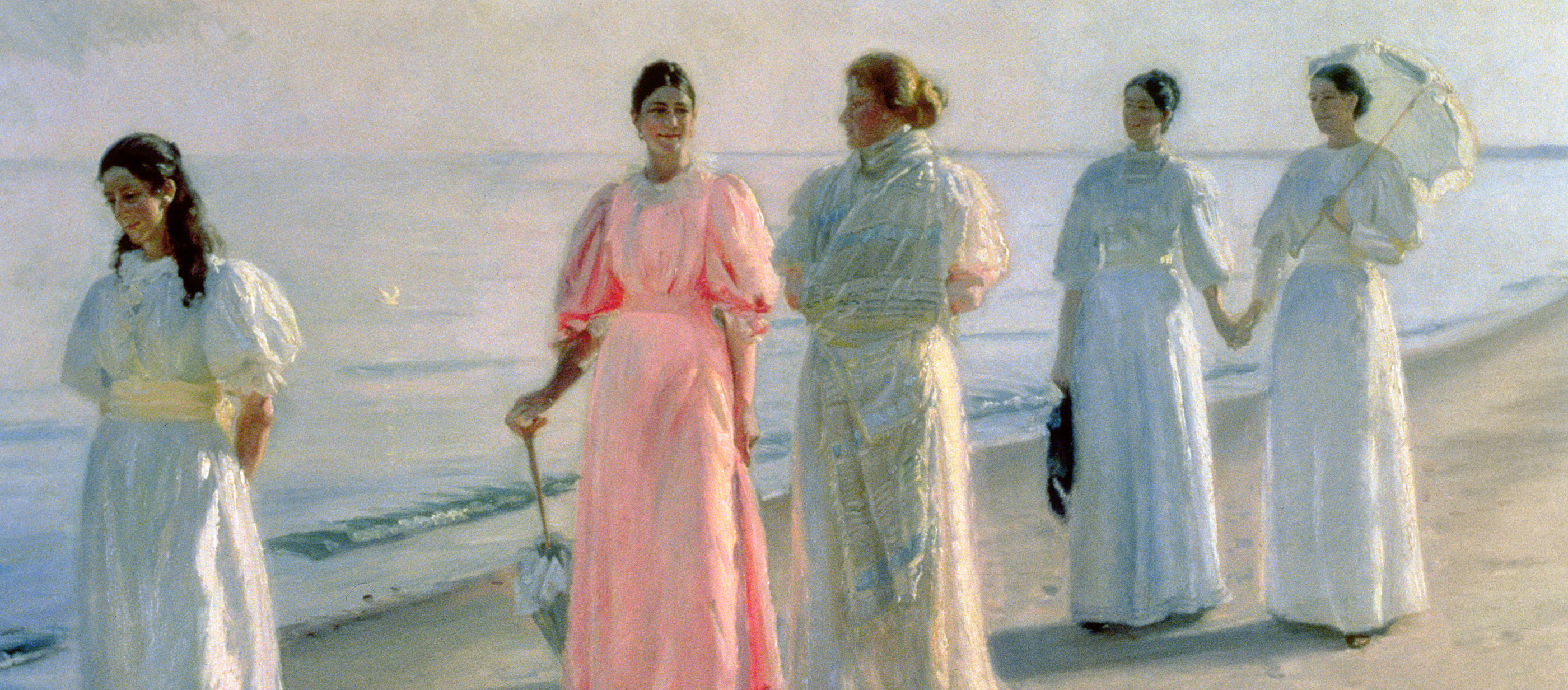

Promenade on the Beach , by Michael Ancher, c. 1896. Skagens Museum, Denmark.

Modern examination of the Greek sense of color began with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who concluded in his Theory of Colors , published in 1810, like Gladstone after him, that Greek color perception was simply defective. Others looking beyond the Greeks to the ancient world in general discovered astonishing lapses, including the total absence in any ancient text of reference to the sky as blue. Blue, it was theorized, is rare in nature—few people have blue eyes, blue plants are rare—and so this uncommon, difficult to replicate color went unrecognized. Yet the ancient world knew of, and coveted, lapis lazuli; and flowers, such as the cornflower and flax, are in fact blue.

Rather than being ignorant of color, it seems that the Greeks were less interested in and attentive to hue, or tint, than they were to light. As late as the fourth century bc , Plato named the four primary colors as white, black, red, and bright, and in those cases where a Greek writer lists colors “in order,” they are arranged not by the Newtonian colors of the rainbow—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet—but from lightest to darkest. And the Iliad contains a broad, specialized vocabulary for describing the movement of light: argós meaning “flashing” or “glancing white”; aiólos , “glancing, gleaming, flashing,” or, according to Cunliffe’s Lexicon , “the notion of glancing light passing into that of rapid movement,” and the root of Hector’s most defining epithet, koruthaíolos —great Hector “of the shimmering helm.” Thus, for Homer, the sky is “brazen,” evoking the glare of the Aegean sun and more ambiguously “iron,” perhaps meaning “burnished,” but possibly our sense of a “leaden” sky. Significantly, two of the few unambiguous color terms in the Iliad , and which evoke the sky in accordance with modern sensibilities, are phenomena of light: “Dawn robed in saffron” and dawn shining forth in “rosy fingers of light.”

So too, on close inspection, Homeric terms that appear to describe the color of the sea, have more to do with light. The sea is often glaukós or mélas . In Homer, glaukós (whence glaucoma ) is color neutral, meaning “shining” or “gleaming,” although in later Greek it comes to mean “gray.” Mélas (whence melancholy) is “dark in hue, dark,” sometimes, perhaps crudely, translated as “black.” It is used of a range of things associated with water—ships, the sea, the rippled surface of the sea, “the dark hue of water as seen by transmitted light with little or no reflection from the surface.” It is also, as we have seen, commonly used of wine.

Seaward ho! Hang the treasure! It’s the glory of the sea that has turned my head.

So what color is the sea? Silver-pewter at dawn; gray, gray-blue, green-blue, or blue depending on the particular day; yellow or red at sunset; silver-black at dusk; black at night. In other words, no color at all, but rather a phenomenon of reflected light. The phrase “winelike,” then, had little to do with color but must have evoked some attribute of dark wine that would resonate with an audience familiar with the sea—with the póntos , the high sea, that perilous path to distant shores—such as the glint of surface light on impenetrable darkness, like wine in a terracotta vessel. Thus, when Achilles , “ weeping, quickly slipping away from his companions, sat/on the shore of the gray salt sea,” stretches forth his hands toward the oínopa pónton , he looks not on the enigmatic “wine-dark sea,” but, more explicitly, and possibly with more weight of melancholy, on a “sea as dark as wine.” Since the Greek happens to use two different words for sea in this particular verse— háls , the salt sea, as well as póntos —the English rendering is best stretched even further:

But Achilles, weeping, quickly slipping away from his companions, sat on the shore of the gray salt sea, and looked out to depths as dark as wine.

If communication and trade, the bulwarks of Greek civilization, were seaborne, so were disaster and ruin. The war at Troy was caused, as Hector sharply reminds his brother Paris, when he, Paris, carried Helen off across the sea:

“Were you such a man when in seagoing ships you sailed the ocean, assembling trusty companions, and mingling with foreign men led away a beautiful woman from a distant land—a woman related to spearmen— mighty ruin to your father and city and all your people, but great joy to our enemies and disgrace to yourself?”

Later, Helen, remorseful, fantasizes about a seaborne deliverance that could have averted the hated war. “Brother-in-law, of me, an evil-thinking dog that strikes cold fear,” she says to Hector, on what would be the last day he would spend in the city of Troy:

“Would that on the day when first my mother bore me, some foul-weather storm of wind carrying me had borne me to a mountain or a swelling wave of the tumultuous sea, where the wave would have swept me away before these deeds had happened.”

That the sea brings destruction is a truth of history as well as poetry. The Greek Bronze Age that Homer described collapsed around 1200 bc for reasons still debated, but records of the time make anxious reference to “sea peoples” or raiders from the sea. A hint of coming menace is preserved on a clay tablet from the palace archive of Pylos, on the coast of the southwestern Peloponnesus. The palace, it appears, was burned down by the enemy; the inscribed clay tablet, baked in the ensuing blaze, survived because of the conflagration. “Watchers on guard over the coastal lands,” the tablet reads, in the Linear B script of the Mycenaeans. Lists of deployments, of men and places, follow: “Detachment of Maleus at Owitono…thirty men from Oikhalia to Owitono, and twenty…men from Apuka…” One can picture them, those lookouts on the coast, armed, on high alert, staring out to the horizon of a sea as dark as wine.

Contributor

Caroline Alexander

Caroline Alexander is an author and a journalist who has written for The New Yorker , Granta , Condé Nast Traveler , Smithsonian , and National Geographic . She is the author of Lost Gold of the Dark Ages , The War that Killed Achilles , and, most recently, a new translation of the Iliad , published by Ecco in 2015.

Back to Issue

- Next Around Alone By Maggie Shipstead

Related Reads

1709 | london, man’s best friend.

Alexander Pope greets a very good boy. More

From the Archives

Friedrich Nietzsche, Robert Caro, Niccolò Machiavelli, Vladimir Nabokov and more...

"A master at accumulating and assembling quotidian materials to create art objects that also serve as uncommon altars and shrines to our past...these ships are suspended in one continuous current that moves tpwards the gallery's windows as if pouring out onto the bustling cityscape of midtown Manhatten. Floating on this tide are scraps and treasures from our shared histories which have left indelible imprints on our national narratives, even as we erase them from our concious thoughts...Locke offers us a maritime procession - at once celebratory and funereal - that is animated by the sub-marine pulse of history...a synthesis of symbols from intertwined historical and cultural legends and narratives...disparate legacies that surf the waves." - Zoe Lukov, Faena Art 'The wine dark sea’ is a description of the Mediterranean used by Homer throughout The Odyssey , and the phrase is repeated by Derek Walcott in his epic poem Omeros, set mainly in the Caribbean and referencing characters from The Iliad . This visual poem incorporates customised models of contemporary and historically resonant vessels - clippers and cargo ships, battleships and lifeboats - filled with hope, potential prosperity and gratification, as well as despair, anguish, and suffering. A ship is a symbolic object; vessel of the soul, means of escape, both safety and danger. No crew are visible - the boats themselves stand for crew and passengers.

C larkesworl DScience fiction & fantasy magazine.

FOLLOW US ONIssue 76 – January 2013 Non-Fiction The Wine-Dark Sea: Color and Perception in the Ancient Worldby Erin Hoffman “And jealous now of me, you gods, because I befriend a man, one I saved as he straddled the keel alone, when Zeus had blasted and shattered his swift ship with a bright lightning bolt, out on the wine-dark sea.” —Homer, The Odyssey, Book V Perception is a funny beast. Homer’s “wine-dark sea” has puzzled scholars for centuries , leading to such far-flung hypotheses as strange weather effects, air pollution, and mass Grecian color-blindness . It’s a phrase repeated in the works of W. H. Auden, Patrick O’Brian, and Brian Jacques, among others. Reading it today, we naturally assume that it is intended as allegory, some evocative reference to the sea’s mystery, its intoxication. We may never know for sure, but one peculiar fact casts the mystery in an interesting light: there is no word for “blue” in ancient Greek. Homer’s descriptions of color in The Iliad and The Odyssey, taken literally, paint an almost psychedelic landscape: in addition to the sea, sheep were also the color of wine; honey was green, as were the fear-filled faces of men; and the sky is often described as bronze. It gets stranger. Not only was Homer’s palette limited to only five colors (metallics, black, white, yellow-green, and red), but a prominent philosopher even centuries later, Empedocles, believed that all color was limited to four categories: white/light, dark/black, red, and yellow. Xenophanes, another philosopher, described the rainbow as having but three bands of color: porphyra (dark purple), khloros, and erythros (red). The conspicuous absence of blue is not limited to the Greeks. The color “blue” appears not once in the New Testament, and its appearance in the Torah is questioned (there are two words argued to be types of blue, sappir and tekeleth, but the latter appears to be arguably purple, and neither color is used, for instance, to describe the sky). Ancient Japanese used the same word for blue and green (青 Ao ), and even modern Japanese describes, for instance, thriving trees as being “very blue,” retaining this artifact (青々とした: meaning “lush” or “abundant”). It turns out that the appearance of color in ancient texts, while also reasonably paralleling the frequency of colors that can be found in nature (blue and purple are very rare, red is quite frequent, and greens and browns are everywhere), tends to happen in the same sequence regardless of civilization: red : ochre : green : violet : yellow—and eventually, at least with the Egyptians and Byzantines, blue. “Why then 'tis none to you; for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” — Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2 Blue certainly existed in the world, even if it was rare, and the Greeks must have stumbled across it occasionally even if they didn’t name it. But the thing is, if we don’t have a word for something, it turns out that to our perception—which becomes our construction of the universe—it might as well not exist. Specifically, neuroscience suggests that it might not just be “good or bad” for which “thinking makes it so,” but quite a lot of what we perceive. The malleability of our color perception can be demonstrated with a simple diagram, shown here as figure six, “Afterimages” . The more our photoreceptors are exposed to the same color, the more fatigued they become, eventually giving out entirely and creating a reversed “afterimage” (yellow becomes blue, red becomes green). This is really just a parlor trick of sorts, and more purely physical, but it shows how easily shifted our vision is; other famous demonstrations like this selective attention test (its name gives away the trick) emphasize the power our cognitive functions have to suppress what we see. Our brains are pattern-recognizing engines, built around identifying things that are useful to us and discarding the rest of what we perceive as meaningless noise. (And a good thing that they do; deficiencies in this filtering, called sensory gating, are some of what cause neurological dysfunctions such as schizophrenia and autism.) This suggests the possibility that not only did Homer lack a word for what we know as “blue”—he might never have perceived the color itself. To him, the sky really was bronze, and the sea really was the same color as wine. And because he lacked the concept “blue”—therefore its perception—to him it was invisible, nonexistent. This notion of concepts and language limiting cognitive perception is called linguistic relativism, and is typically used to describe the ways in which various cultures can have difficulty recalling or retaining information about objects or concepts for which they lack identifying language. Very simply: if we don’t have a word for it, we tend to forget it, or sometimes not perceive it at all. The famed neuroscientist Dr. Oliver Sacks (you might know him as Robin Williams’s character in Awakenings ) described a poignant example of linguistic or conceptual relativism with regard to schizophrenia. Accounts of the disease prior to the 19th century are rare, and none at all exist in ancient literature (as opposed to “madness,” which was documented, but primarily concerned aimless wandering and spontaneous violence). The broad classification of “madness” persisted well through the 19th century, with schizophrenia identified in the early twentieth, and still considered rare through the middle of the century. When Sacks began practicing in 1965 in New York City, and in particular began studying disorders related to schizophrenia, he was shocked by a gradually increasing awareness that the disease was not nearly as rare as the science of the day claimed—especially among the homeless. Importantly, the clinical assumption that “schizophrenia is rare” was reinforcing the rarity of its diagnosis, to the point of blinding doctors to what was right in front of them. These blooms in diagnosis—we have been for the last ten years experiencing a bloom in autism recognition—have as much to do with clinical perception as they do with the actual physical incidence of the conditions. On a lighter note, Sacks also recently recalled that the most magnificent thing he had ever seen in his life was a field of yellow, seen while he was—is it appropriate to say a famous neuroscientist was high ? Say rather that he was conducting experiential research in a varied state of neurochemical condition! But however you slice it, he says it was the most yellow yellow he had ever seen or expects to see again, a yellow beyond description, a yellow of interstellar radiance and the breath of ancient gods. It isn’t the first time that Dr. Sacks has discussed color and altered states: in “The Dog Beneath the Skin,” he tells the infamous story of the 22-year-old medical student who, under the influence of PCP and amphetamines, enters a week-long heightened state of awareness. Among other things, this student—decades later revealed to have been Sacks himself, of course—perceived “dozens of browns” where previously he had seen only one shade. (Dr. Sacks does not now recommend this type of student experimentation.) This particular super-sensory color perception is, too, reminiscent of another physical condition related to color: tetrachromacy. Most humans are trichromatic, possessing three types of color-sensing cone cells—but an undetermined percentage of women, as well as almost all birds, are tetrachromatic, possessing four receptor types. Tetrachromats perceive a kind of fourth primary color, usually a blue-green, that gives them a heightened ability to distinguish between shades of color, often to the point of distinguishing separate shades where a trichromat will perceive identicality. “The evolution of sense is, in a sense, the evolution of nonsense.” —Vladimir Nabokov, novelist, synesthete We need not travel far to determine whether these enhanced states of perception—which, given that we remain the same species as Homer, can be societal or psychological in their impetus—can impact our worldview, or our creative selves. We know that people with synesthesia , a neurological anomaly in which one sensation “bleeds” into other sensations, are eight times more likely to pursue careers in the arts than non-synesthetes. Synesthesia comes in many varieties, but those with a visual variant (for instance perceiving numbers and letters in colors) are more likely to become visual artists—or novelists. Vladimir Nabokov, novelist and synesthete, wrote his synesthesia into his characters on occasion, and some of his descriptions—such as the word “loyalty” suggesting “a golden fork lying in the sun”—indicate that this crossing of senses, infused with color, certainly influenced Nabokov’s construction of language. Words themselves could be beautiful or garish depending upon their letter-level construction. Some scientists have postulated that this phenomenon of carrying meaning from one sense into another—which is essentially the definition of a metaphor—is universal and contains insight into the deepest workings of our minds. In the case of the common grapheme-color synesthesia, such as Nabokov’s, a likely explanation is the close proximity of portions of the fusiform gyrus that deal respectively with word and color recognition in the brain. When a synesthete reads a word, some of the electrical energy from that word-recognizing region is possibly leaping over into that color recognition region. One remarkable side effect of this is that many synesthetes tend to perceive the same colors for letters (“A” tends to be red), which underscores the structural theory—and might suggest that this same phenomenon is at work in all of us below the level of our conscious awareness. While the causes of synesthesia remain unknown, it is generally agreed that the physical basis is a kind of excess of interconnectedness between neurons. It may be that the “pruning” we undergo as children does not complete, leaving connections behind that in the mainstream population are eradicated—but provoked synesthesia in the cases of drug use or epileptic seizures suggest that non-synesthesian brains are capable of synesthetic effects. A 1929 experiment by Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Köhler elegantly illustrates what some call our natural synesthesia. Köhler drew two random shapes: one spiky and sharp, the other flowing and rounded. He then asked subjects to guess of these shapes which one was called “kiki” and which was called “bouba.” The results were very clear: 95-98% of subjects identified the sharp shape as “kiki” and the rounded shape as “bouba.” (Fascinatingly, autistic individuals make this match only 56% of the time.) Köhler’s experiment wrapped science around what we would call onomatopoeia: when a word sounds like what it is. But onomatopoeia is by definition synesthesia, the transference of sound into orthogonal meaning. The modern neuroscientist Dr. Vilayanur Ramachandran suggests that Köhler’s experiment shows that, to a certain extent, we are all synesthetes, and further that this inherent interconnection between our cognitive functions is intrinsic to the most beloved traits of humanity: compassion, creativity, ingenuity. What, after all, is an idea, but one flash of thought leaping across the mind to suggest novel possibility? “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” —Aristotle So, if we’re all synesthetes, and our minds are extraordinarily plastic, capable of reorienting our entire perception around the addition of a single new concept (“there is a color between green and violet,” “schizophrenia is much more common than previously believed”), the implications of Homer’s wine-dark sea are rich indeed. We are all creatures of our own time, our realities framed not by the limits of our knowledge but by what we choose to perceive. Do we yet perceive all the colors there are? What concepts are hidden from us by the convention of our language? When a noblewoman of Syracuse looked out across the Mare Siculum, did she see waves of Bacchanalian indigo beneath a sunset of hammered bronze? If a seagull flew east toward Thapsus, did she think of Venus and the fall of Troy? The myriad details that define our everyday existence may define also the boundaries of our imagination, and with it our dreams, our ethics. We are lenses moving through time, beings of color and shadow. Erin HoffmanErin Hoffman is an author and game designer from California. Her fantasy series The Chaos Knight completes with its third volume, Shield of Sea and Space, in May 2013 from Pyr Books. PURCHASE THIS ISSUE: Amazon Kindle Amazon Print Edition Weightless EPUB/MOBI/PDF  Audio Fiction Awards & Recognition Authors & Artists Random Story Random Podcast Follow Us On SUBSCRIBE AT B&N Nook Newsstand ClarkesworldCitizens Weightless Books ISSN 1937-7843 · Clarkesworld Magazine © 2006-2024 Wyrm Publishing. Robot illustration by Serj Iulian.   a journal of research & art

The Wine Dark SeaThis is part of our special feature, Networks of Solidarity During Crises. “The Wine Dark Sea” is a description of the Mediterranean used by Homer throughout The Odyssey, and the phrase is repeated by Derek Walcott in his epic poem Omeros, set mainly in the Caribbean and referencing characters from The Iliad. This visual poem incorporates customised models of contemporary and historically resonant vessels—clippers and cargo ships, battleships and lifeboats—filled with hope, potential prosperity, and gratification, as well as despair, anguish, and suffering. A ship is a symbolic object; vessel of the soul, means of escape, both safety and danger. No crew are visible—the boats themselves stand for crew and passengers. “The Wine Dark Sea” is a selection of up to thirty-four boats, either hanging or on strands, ranging from 23 to 183 cms in length.  Hew Locke was born in Edinburgh, UK, in 1959; lived from 1966 to 1980 in Georgetown, Guyana; and is currently based in London. He obtained a B.A. Fine Art in Falmouth (1988) and an M.A. Sculpture at the Royal College of Art, London (1994). In 2000 he won both a Paul Hamlyn Award and an East International Award . His work is represented in many collections including those of the The Government Art Collection, The Pérez Art Museum Miami, The Tate Gallery, The Arts Council of England, The National Trust, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, 21c, The New Art Gallery Walsall, The Victoria & Albert Museum, The Imperial War Museum, The British Museum and The Henry Moore Institute, Leeds. These images are Courtesy of Hew Locke and P·P·O·W, New York Published on October 13, 2020.  Allegria by Giuseppe Ungaretti  Bard College Border Pedagogy: Experiential Learning, Syllabi, and a Model…  © 2016-2024 EuropeNow. All Rights Reserved.

Your shopping cart is empty!

Sailing down the wine dark sea How hard can it be for modern Greeks, as well as foreign scholars, to solve an almost 3000 years old riddle? For those who have chosen to cross the seas by boat to get to their vacation destination this summer, this riddle will show up on the waves’ foam while they will be gazing the sea’ s blue colour.  While it may seem distant and unequal, Homer sets the ever-wanderer Ulysses on the same water, gazing himself the blue colour od the sea from his ship’ s gunwale on his way to Ithaca. However, the ancient bard, who possibly travelled as well by boat through the Greek seas, offers a different description on the sea’ s colour from what we all have in mind. From the very first lines of Odyssey, Homer recites that the hero sails down the “wine dark sea” (epi oinopa ponton). This verse is often repeated throughout Odyssey raising questions in all modern scholars of wine history, and, to this day, is still an unanswered riddle. Over the past 150 years, a lot of the secrets of wine have been revealed and now constitute common ground. Many researchers have used this knowledge in order to cast away the haze of time, covering with mystery the production of wine in ancient Greece. Despite science’ s achievements, the question still remains: what kind of variety or method could have been used to produce a red wine whose colour was compared with the colour of the sea as Homer describes? Acknowledging that viticulture in the Aegean and Ionian islands is a continuous – historically – tillage, it would not be daring to say many of the varieties that are present today on the islands have originated from Homer’ s time. Thus meaning, the first attempt to interpret the riddle would be the search of that specific variety, growing in the Aegean and Ionian islands, that could ascribe such a deep violet colour to the wine. Avgoustiatis, Vertzami, Kotsifali, Liatiko, Limnio, Mandilaria and Mavrodafni give from garnet to purple coloured wines, yet none of them resemble the colour of the sea, so the explanation must lie elsewhere. Another interpretation that many scholars espoused occasionally but not adopted massively, was the philological approach of the riddle. The bard likes to perplex things given that throughout Odyssey he often describes the wines that are being consumed. So, he recounts drinking sweet wines with their colour ranging from red (erythron oinon) to deep dark brown (aithopas oinos), but in no case deep blue. A further problem the scholars must surpass is the ancient Greek tradition that depicts Homer as blind, making every attempt of verse interpretation even more difficult. Some readings conclude that the “wine dark sea” is some poetic technique that served Homer in his recite. Others refer to the proverb as the delineation of the calm sea that was taken as a sign for a safe journey. Some scholars decided to travel by boat through the Greek seas to be able to witness with their own eyes Homer’s lyrics. They are responsible for the theories relating to the water’s colour on the point where the seas merge, and with the purple colour of the sea when the sun sets and dives in it. What both theories ignore is the saying “the sea is blue, but the wind blackens it”. A bolder explanation the present text espouses refers to the specific sociological characteristics that rule the seas that surround us since then. It is speculated that Homer came from the east side of the Aegean, with many cities of Ionia and Aegean islands wrangling over his origin. On the other hand though, Alcinous, kind of the Phaiacians on the island of Corfu, explains to Ulysses that there are no people like the Phaiacians, who are the best seafarers as well as singers and revelers. This undimmed spirit survives to our days and remains imprinted on the well-known Heptanesian song saying “ [wishing] the sea were wine and the mountains savories and the boats wine glasses for the revelers to drink from” Could Homer have been influenced from this when he was describing the wine dark sea? For those of you, who will be at the Aegean and Ionian islands, bear in mind that there are many choices from indigenous varieties to taste and savor. White and rose wines might be the undisputed kings of the Greek summer, nevertheless lightly cool red wines from the islands’ indigenous varieties could accompany harmonically your meals. For those of you who seek a summer reading, we dare you to find a case throughout Odyssey in which the wine being offered is not red. Ulysses surely knew something, sharp as a needle as he was. Special thanks to Greece’s eternal friend, Eckhart Koch , for his incitement to read Odyssey again. Kostas Prova tas Greece and Grapes

Book Review: “The Wine-Dark Sea” by Leonardo SciasciaWhenever I move to a new country, I not only read guidebooks and history books, but I also try to find some novels and stories which portray my new domicile, whether in its contemporary age or in the past. When I moved to Sicily , one of my clients mailed me a copy of Leonardo Sciascia’s short story collection The Wine-Dark Sea .  The Long Crossing describes a 12-day journey by Sicilian émigrés, huddled under the deck of a boat whose captain promised to take them to America. (The stories were written between 1959 and 1972.) The Sicilians hoping for a better life have sold all of their belongings to pay for the passage. The more clever ones have taken out loans, knowing that they wouldn’t be around when the loan would become due. They have written down the names and addresses of relatives in the USA. They are optimistic. When they land 12 nights later and go on shore, they soon reach a road and remark its good surface, “but to tell the truth they found it neither as wide nor as straight as they had expected.” They are surprised to see so many Fiat cars. Finally they flag down a driver to ask for directions for Trenton, New Jersey, and only when the driver curses at them in Sicilian, the émigrés realise that they have just spent their life’s savings to be taken to the other end of Sicily. They sit down because “there was, after all, no need to hurry back.” In Philology , two Mafiosi discuss the etymology and the meaning of the word “Mafia”, reverting to other languages from Arabic to French, to dictionaries and the opinions of learned men, before one of the gangsters concludes: “Culture, my friend, is a wonderful thing.” The Test describes the travels of a Swiss recruiter who is hiring Sicilian girls for a factory in Switzerland. My favourite story has to be End-Game . A husband has hired a killer to finish off his wife. As the killer enters the marital home, he is shocked to see that the wife has been waiting for him. It turns out that she is much cleverer than her husband, and has not only seen through his plot, but has also devised a plan to convince or blackmail the killer into accepting her proposition to kill the husband instead. Her devious plan goes beyond that even. This is a very smart crime story with hilarious dialogue. The title-giving story The Wine-Dark Sea is the longest one in the book, but no less captivating than the others. Describing a long train journey from Rome to Sicily, the dialogues of the people who randomly get together in a compartment, among them two rowdy but smart children, bring the trip to life as if the reader was sitting there, not able to suppress a smile at the witty exchanges. A romance between two of the passengers evolves, not unnoticed by the others. The discussions between the men reveal the tension between Sicily and the rest of Italy. There is more in these 40 pages than many novels can offer. As the protagonist Bianchi says at the end of the story, when all the others have disembarked and only he continues the journey: “Lord, what a trip!” Enjoy that trip! Get this book, even if you have never been and will never come to Sicily. Some of these short stories are among the best stories in world literature. I forced myself to take a pause of a day or two after each of the stories, to let them sink in and to revel in each one of them. And now, I’ll put the other books by Leonardo Sciascia on my wishlist . Share this:

About Andreas Moser8 responses to book review: “the wine-dark sea” by leonardo sciascia. This sounds like a great book, and I will begin the search for it….chances of it being in the library of Oaxaca, Mexico are slim…Soldotna, Alaska even slimmer. But I know it’s out there somewhere! Thanks for the recommendation. Maybe you should also start a wishlist. Although far fewer people do actually send books than promise to do so. E’ veramente un’ottima idea riprendere Leonardo Sciascia oppure “Il mare del colore del vino” che non conosco ancora. Grazie After some confusion with Patrick O’brian I found it! Thank you. I was born in Germany my mother is still a German citizen. Can I regain my German status? Please have a look at my FAQ on German citizenship law or my infographic on that subject. Pingback: Italy Reading List | The Happy Hermit Pingback: Bücherliste Italien | Der reisende Reporter Please leave your comments, questions, suggestions: Cancel replyIf you find this blog funny, clever or even useful, you can keep it alive with a small donation. Thank you! Recent Posts

Follow Blog via E-MailEnter your e-mail address to follow this blog and receive new posts by e-mail. It\'s free! Email Address:

The Art of a Wine-Dark Sea“Free soul, thou shalt always cherish the sea,” wrote Charles Baudelaire. The sea he means is the Mediterranean, the “wine-dark sea” that worked its magic on writers from Homer to Hemingway and enchanted the most celebrated painters of modern times. Thus the artistic event of the autumn season at the Grand Palais, Paris, called “The Mediterranean, from Courbet to Matisse” presents over 90 paintings, including many chefs d’oeuvres, spanning the second half of the 19th century through the beginning of the 20th century the works of painters whose names resonate through the annals of modern art: Auguste Renoir, Paul Cezanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Paul Signac, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse prominent among them. They represent the major artistic upheavals of the period including Impressionism, Pointillism, Neo-impressionism and Fauvism, in enduring testimonials to the spell that the Mediterranean casts. This was not always the case. Although the Mediterranean, cradle of civilization to the Greeks, had already hypnotized Homer, mid-19th century civilization regarded it as a venue for fashionable winter resorts or sanatoriums where consumptives came to die. The sand and the sea and the sun held little attraction, but with the belated arrival of the French industrial revolution and the concomitant advent of the railroads, the Mediterranean began to attract avant-garde writers who composed lyrical hymns to this watery Eden. Artists were not far behind in discovering a painterly paradise of incomparable luminosity, vibrant colors and ravishing landscapes. The exhibition embraces the coastal region from Catalonia to the Gulf of Genoa, and is divided into nine sections: “Discovery of the Mediterranean Landscape”; “Shores”; “Rocks”; “Mythologies”; “Through the Trees”; “Holiday Resorts”; “Ports, Fishing, Sails”; “Luxuriances”; and “Openings onto the Sea.” Each section presents the expected masterpieces, beautiful and breathtaking, throbbing with joy and sensuality, landscapes flattened by the sun, awash in luminosity, metamorphosed into spheres or cubes or dots or splashes of primary colors. But it also includes picture postcard images, some pleasant surprises, blatant disappointments and lesser but not always uninteresting works of artists who were never able to become truly great. Gustave Courbet’s diminutive painting, The Shore at Palavas, opens the exhibition. It clearly depicts the free soul longed for by Baudelaire, who was a great admirer of this fellow subversive. On a deserted beach, a tiny figure of a man Courbet himself pays homage to the immensity of the sea in a grand gesture of defiance: brandishing his artist’s cap, arm boldly outstretched, an infinitesimal figure challenging the legendary mare nostrum. The sea is calm, yet disturbing with its dark, opaque blue and limitless horizon. The azure sky inhabits half of the painting, thick near the horizon with billowing white clouds, suggesting metaphysical longing. In “Shores,” Cezanne’s L’Estaque, View of the Gulf of Marseilles, along with two other paintings of the Provenal Alps by the same artist on view, thrice proves that he is the master of them all. Here luminosity gives way to structure, forms and subdued colors highlighting the sea as a great triangle cutting into the land and mountains beyond the coastline. Three early works of Picasso attest that he was still searching for his unique inspiration. Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida’s lovely Shadow of the Boat depicts a black shell of a fishing bark and mauve shadows of an invisible sailboat on an undulating sand taken up again in a narrow cloud bank skirting a changing sea. In “Mythologies” Frederic Montenard’s Cemetery in Provence confronts us with the pervasive role death played in a region dedicated to ephemeral pleasure, but which, for many, was the last stop on the way to eternity. Desolate dunes, crosses and graves surround a small boy kneeling, the sea beyond as the hereafter rendered in pale tones. In “Luxuriances,” quintessential impressionist Monet’s The Villa Trees at Bordighera dazzles us with its rainbow palette of pink and blue mountains, vegetation in every hue of green, a triumph of light and color. Matisse’s astonishing exercise in a minimalist, quasi-abstract representation of a French Window at Collioure closes the exhibition. “I have begun to use pure black as a color of light and not as a color of obscurity,” he explained. And indeed, strips of window defined by muted colors of green and blue and gray open onto a deep black plane stretching over half the canvas. In casting off the superfluous, it is the culmination of the artist’s search for “balance, purity, serenity.” We have come a long way from the vast expanse of Courbet’s Mediterranean. In 1854, Courbet saluted the sea with exultation. In 1914 Matisse looked out of a window at the same sea and what did he see? Blackness. More Must-Reads from TIME

Contact us at [email protected] Old Salt BlogA virtual port of call for all those who love the sea , hosted by nautical novelist rick spilman.  When Did the Wine Dark Sea Turn Blue?This is nothing new. Homer referred to the famously blue Aegean as the “ wine dark sea .” When did the wine dark sea turn blue? In the Iliad and the Odyssey , Homer never uses the word “blue” once. William Gladstone, the British prime minister, was also a classical scholar, who wrote 1700-page study of Homer’s epic poetry. In one chapter, he describes Homer’s strange choice of colors. Sheep wool and ox skin are purple. Honey is green, while horses and lions are red. The sky is filled with copper or iron colored stars, but neither the sky, nor the sea, nor anything else in his poetry is ever “blue.” Gladstone was so baffled by this confused yet incomplete rainbow that he theorized that the ancient Greeks must have been not capable of distinguishing color. Science does not support his theory, which, in its day, was met largely with derision. While Gladstone was wondering if the Greek’s were color-blind, a German philologist, Lazarus Geiger , was casting a broader net. He examined ancient texts across a range of cultures, including Icelandic sagas, the Koran, ancient Chinese stories, and Hindu Vedic hymns and an ancient Hebrew version of the Bible. He comments about the Vedic hymns, “ These hymns, of more than ten thousand lines, are brimming with descriptions of the heavens. Scarcely any subject is evoked more frequently. The sun and reddening dawn’s play of color, day and night, cloud and lightning, the air and ether, all these are unfolded before us, again and again … but there is one thing no one would ever learn from these ancient songs … and that is that the sky is blue. ” In many cases, blue was considered a shade of green , gray or purple, but not distinguished as its own color. Gieger observed that the definition and description of color evolved with most cultures over time. Black and white were the first colors designated, followed by red. Yellow and green came next (although in some cultures green came first.) Finally, blue arrived. Some have speculated that this may be because blue is fairly rare in nature. Others have theorized that until a culture is capable of artificially creating the color, they do not distinguish it from other shades. The one ancient culture which had an early word for blue was the Egyptian. The Egyptians also manufactured a blue dye far earlier than anyone else in the world. But to return to the original question — when did the wine dark sea turn blue? The distinction between green and blue in English appears to have begun around the Middle Ages. The modern English word blue comes from Middle English bleu or blewe , from the Old French bleu , a word of Germanic origin, related to the Old High German word blao . But who first called the sea blue? I don’t have a good answer. Shakespeare’s saltiest play, “ The Tempest ,” mentions the sea over 30 times, water over a dozen and waves around four, yet only once does Shakespeare mention the color of the sea. “…’ twixt the green sea and the azured vault. ..’ Shakespeare identifies the sky as blue (or at least azure) while the sea remains green. Based on a word search on Open Source Shakespeare , the bard did describe the sea as silver as well as green, but never did he call it blue. Google has a search feature, the Ngram Viewer , that allows searching for words or phrases from the books scanned in Google’s library. Searching for “blue sea” and “blue water” between 1500 and the year 2000, suggests that the prior to around 1700, there were few mentions of the sea as blue. No one could see the color blue until modern times Why Isn’t the Sky Blue? When Did the Wine Dark Sea Turn Blue? — 5 CommentsI saw the dress as either tan or dark brown and white stripped or light blue stripped. I did not see gold. No matter what color you think you saw, the fact remains. The dress is ugly! The Minoans used abundantly blue decorative motifs in Knossos 4000 years ago. From what I have read, the Minoans acquired blue dyes from the Egyptians and that the Phoenicians acquired it from the Minoans, who later brought it to Mycenae. Pingback: Coloring Perception. | loonmusings Read ‘Through the Language Glass darkly’ by Guy Deutscher and find out Why The World Looks Different In Other Languages. It’s brilliant. September 16, 2024 North West Island to AirlieSorry it has taken me so long to get around to this post. It’s not like I can blame my hectic lifestyle. My pilgrimage to Sarah’s resting place complete, I was called back to reality by the need to get back within communication range for a video conference the next morning. I weighed anchor and […] Bundaberg to North West IslandI had been weighing up a few options for this next leg. Do I do a short hop to Pancake Creek or Lady Musgrave? Or a longer leg directly to North West Island. Frankly it came down to not wanting to spend any more time with my keel in the mud at Bundberg. At its […] Mooloolaba to BundabergWith the handover of the Sydney Football Stadium imminent, I could start my long 2 months of live-aboard. Joining me for that last overnight passage for a while, around Fraser Island, was long time crew and ex-work colleague Doug Rayment and girlfriend Sascha EE. This would be the first overnight sea passage on a sailing […] Southport to MooloolabaLindy Hardcastle joined me for the short trip from Southport to Mooloolaba. I flew up on Sunday morning and met up with my uncle, Steve, and my cousin, Sean. The later of which works for Riviera yacht on the Gold Coast. The place was pumping, so much so the yacht club couldn’t accommodate us for […] Sydney to Southport SoloThis year the delivery of Wine-dark Sea to Queensland for Airlie beach race week and magnetic island race week is being juggled with the final commissioning of the new Sydney football stadium. Eyeing up a potential 5 day weekend without commissioning and a favourable weather window, on the tail of a southerly blast, I decided […] Getting ready to rumble…It feels great to be getting back into the routine. As departure approaches I’m now in my route planning routine. Every 12 hours, when the new forecasts are released, I download the 6 models from Predictwind and import them into Expedition to run my optimized routes at 6 hour departure times. Currently I’m debating slightly […] Modifications aplenty. Some planned, some not so muchSo long since my last post. Well I didn’t seem to get out much on the boat over summer. Not really sure why. The general blur of the last 2 years of the ‘rona has me wondering what exactly I have done with the last 2 years. I even had to Google when we came […] Here we go again……a little scaled back though. Today we finally start the 2021-2022 sailing season. I’ve decided to back my racing off for a few reasons, so I am only planning to do Friday twilights. I might throw in a regatta here and there depending on crew interest. One of the main reasons was that over the […] Sorry its been so long…….but COVID has made a right mess of things for all of us hasn’t it. So what’s been happening? (I can’t believe my last post was for Sarah’s birthday last year) At that time I was newly installed in my brand-new-second-hand apartment in Dee Why. I’m well settled in now and have ripped up the […] Happy Birthday SarahToday would have been Sarah’s 56th birthday. Today I feel her loss as keenly as the day she was taken from us all too soon. I can’t help but think what we would have been doing. I suspect we would have, as I have this morning, gone down and watched a beautiful sunrise over the […]

Noakes Sydney Gold Coast Yacht Race 2024Wine-dark sea (th). /media/3445938/wine-dark-sea-6188.jpeg) Competitor Details

Full Standings available approximately three hours after the start. OFFICIAL CYCA - Helly Hansen MERCHANDISEShop the official CYCA - Helly Hansen clothing range in person at the Club in New South Head Road, Darling Point or online below. From casual to technical clothing, there is something for all occasions. Be quick as stock is limited.  The wine-dark seaby Mariska Buitendijk | May 27, 2020 | News | 0 comments  The KNVTS has a proud tradition to connect its vision on the future with a view on the historic past of shipbuilding practice. Time for the chair of the KNVTS Ship of the Year Committee Rien de Meij to take a step back and reflect on the idea of “vision”. Here is the story of “The wine-dark sea”. The vase from Cerveteri of which a detail is presented below, is dated ca. 520 BCE. The purpose of the vase was to mix wine and water for a group of merry men, sitting orderly to listen while the table is loaded with bread and meats. The cup-bearer draws wine and fills the cup for every guest at the drinking party [ sumpósion ]. Let’s take a glimpse over the rim of this Terracotta column- kratēr . The inside of the rim is decorated with three ships, equally spaced, the filling ornament between each two ships being a dolphin. Imagine the vase being filled with dark wine: the three ships sailing through a wavy sea, in endless pursue of each other. The wine and the painting bring to light and life the Homeric metaphor of ships on a “wine-dark sea” [ oinops pontos ]. The snout-shaped cutwater [ steira ] protrudes in front of the stem contour, lengthening the water lines and reducing the angle of entrance, making the ship qualify as “swift” [ thoísin ]. The stem post is straight-horned [ orthokrairáon ]. The sides of the red-cheeked prow have once been baptized with red wine. The hull of this merchant ship with its large freeboard is black and huge. Horizontal white lines over the hull represent the strakes of the gunwale planking. The sail is rigged like window blinds. The brails [ kálos ] were made fast to the foot of the sail [ histíon ] and were rigged through fairleads along the forward surface of the sail. From there, they were run over the yard and to the stern. Letting out full sails is done by slackening off on every brail. The oversized steersman [ kubernētēs ], seated on a bench [selma] on the raised half-deck [ íkria ], handles the tillers [ oiáklon ] of the twin rudder-oar [ pēdálion ] The stern post carries an in-board facing bird-head decoration [ aphlaston ]. There is a version of Euripides’ tragedy Alkestis (438 BCE) – that is played in an opera of Jean-Baptiste Lully (1674 CE) – which begins at the wedding of Admetus and Alkestis: ‘An undeclared suitor, Hēraklēs, prepares to leave Lolcos. A jilted suitor, Lykomedes, abducts Alkestis under the guise of giving a party for the betrothed couple; his escape is aided by a storm at sea: the sea-nymph Thetis, sister of Lykomedes, rises from the sea on a marine chariot and at her command the four winds start to blow. However, the wind god Aeolus calms the sea, allowing Admetus army (including Hēraklēs) to pursue Lykomedes’ ship. Hēraklēs triumphs and delivers Alkestis, but Admetus is mortally wounded.’ Artemis was involved too; at the wedding, Admetus forgot to make the required sacrifice to Artemis and found his bed full of snakes. In this interpretation, the three ships depicted on the inside of the rim of the kratēr may represent the pursue of Lykomedes by Hēraklēs, in which Hēraklēs triumphs. The decorations on the side of the vase narrate the story of the Struggle for the Tripod: Lykomedes in a chariot, Artemis; Iolaos in a chariot, Athena; Hermes, Dionysus, gods and goddesses. Dionysus cupThe wine in the vase will be used to fill the drinking cups of the guests at the drinking party. Such a cup is depicted in the next figure; it is the Dionysus cup [ kylix ] which is dated ca. 530 BCE. The front side of the cup shows how Dionysus looks you in the eyes, when you lift the cup for drinking. The backside of the vase shows a defeated person, possibly a Scythian, threatened by soldiers who are ready to kill the grounded person. The images around the handles probably depict the battles for the corpses of Patroklos and Achilles, with the naked corpse being Patroklos.  The Dionysus cup – side view focusing on the stylized face. How would such drinking work? Trying to get the picture, you can firstly see the ships of Hēraklēs and Lykomedes sailing through the dark wine that fills a large kratēr to the brim. After the wine is poured into your kylix , the eyes of Dionysus stare at you from the side of it, invitingly. You accept the cup and while you start drinking, Dionysus breaks through the surface of the wine, sitting on a ship that travels directly towards your mouth (figure below). The drinker drinks the wine and closes in to the god who leaves him incapable of speaking letters in the right order. Here is what Antiphanes said about it: I’m not too drunk to think, but just enough that it is hard to form any letters with my mouth The ship in the cupThe next image shows the decoration on the inside of the Dionysus cup. It shows Dionysus in a ship, sailing among dolphins. From the mast foot grows a vine.  The Dionysus cup – top view focusing on the ship of Dionysus. The curves of the ship start with the silhouette of the straight-horned [ orthokrairáon ] stem post. The forebody then projects far forward into the shape of a snout-shaped cutwater [ steira ]. The pointed snout, or embolos , is decorated with a pair of eyes [ ophthalmós ]. The bow is fitted with a closed railing, which continuous towards aft as an open railing mounted to vertical struts. The shoulders of the ship, both fore and aft, have been decorated with a dolphin. On the cutwater we see the eyes [ ophthalmós ] of the ship that either look straight ahead to scare of the enemy, or look sideways to ward off the evil eye that will cause misfortune or injury. The contour then continuous towards the aft, a slight discontinuity in the fairing of the lines, in the location where the lower contour of the snout-shaped bow moves over in the keel line, suggest that the snout-shape is an appended feature; not a part of the bare hull itself. The curved keel line runs into the rounded shape of the stern of the ship. The curve of the keel makes her more suitable for beaching stern-first than vice-versa. The stern quarter (right) carries a steering-oar and a boarding ladder [ apobáthra ] or lading plank . The stern post curves forward, giving the boat her characteristic scorpion-like contour. The decorations on the Dionysus cup may help to envisage the image of the ancient Greek ship, however mostly she was a point of departure for seamen in a pensive mood, considering the pros and cons of getting drunk. Picture (top): Detail of interior of Attic black-figured cup from Cerveteri (c. 520 BCE). AcknowledgementsThis story could only be formed thanks to the CHS Oinops Study Group of the online community for Classical Studies of The Center for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University, guided by Jacqui Donlon. Her work was published, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license at https://kosmossociety.chs.harvard.edu/?p=11283. Where possible, the images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses.

Series of articles