No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

The Different Parts Of A Sailboat Explained

A sailboat consists of hundreds of parts, each with its specific term and function. From stern to bow, keel to mast, each part and its equipment plays a vital role in making the vessel seaworthy and able to sail.

In this guide, I’ll show you most of the components so you can better understand what they are and their function. We’ll begin with the main components, move to the basic features, and finish with our interior and equipment.

The main parts of a sailboat

The main parts of a sailboat are the key components that make it a vessel able to sail. You’ll notice that the structure has several distinct differences from powerboats.

We can categorize the main parts into the following:

- Hull: The main structure, or “body” part of a boat.

- Keel: The heavy fin at the bottom allows stability under sail.

- Rudder: The fin sticking down at the stern, allowing us to steer the vessel.

- Mast: The “spars” or “poles” holding the sails.

- Rigging: The standing rig is the wires that supports the mast. The running rigging is all the lines that control the sails.

- Boom: The horizontal spar supporting the bottom of the mainsail.

- Sails: The canvas used to harness the energy of the wind.

Let’s dig a bit deeper into each of the components.

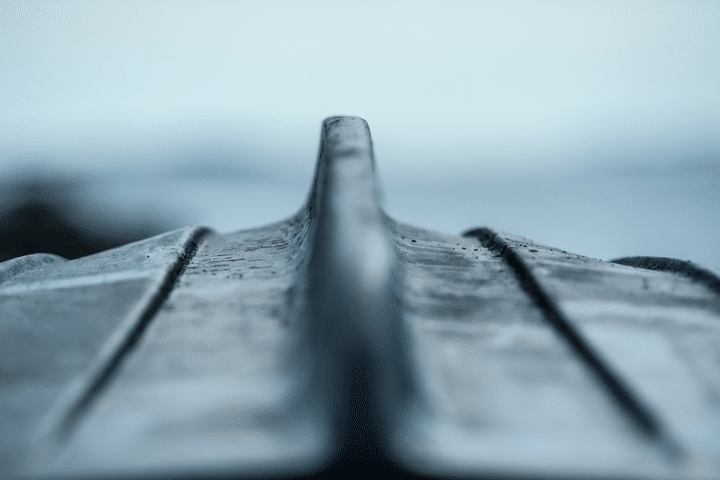

Hull – The main structure

A sailboat’s hull is the vessel’s main body or structure. The shape is vital to the boat’s performance and stability, and you have probably seen boats in many different forms. Older vessels are typically narrow, with a rounded underbody and a small stern. Modern designs have a flatter belly and broad stern supporting dual helm stations.

One of the hull’s primary functions is to displace water and provide buoyancy to keep the boat afloat. The hull is also the structure that holds the vessel’s living compartments and all its equipment. The main structure must be strong enough to withstand the forces of the water and any rough weather conditions that Mother Nature might throw at it.

Fiberglass (GRP), steel, aluminum, and wood are the most commonly used hull materials, each with pros and cons.

You can learn more about hull materials and their strengths in this article .

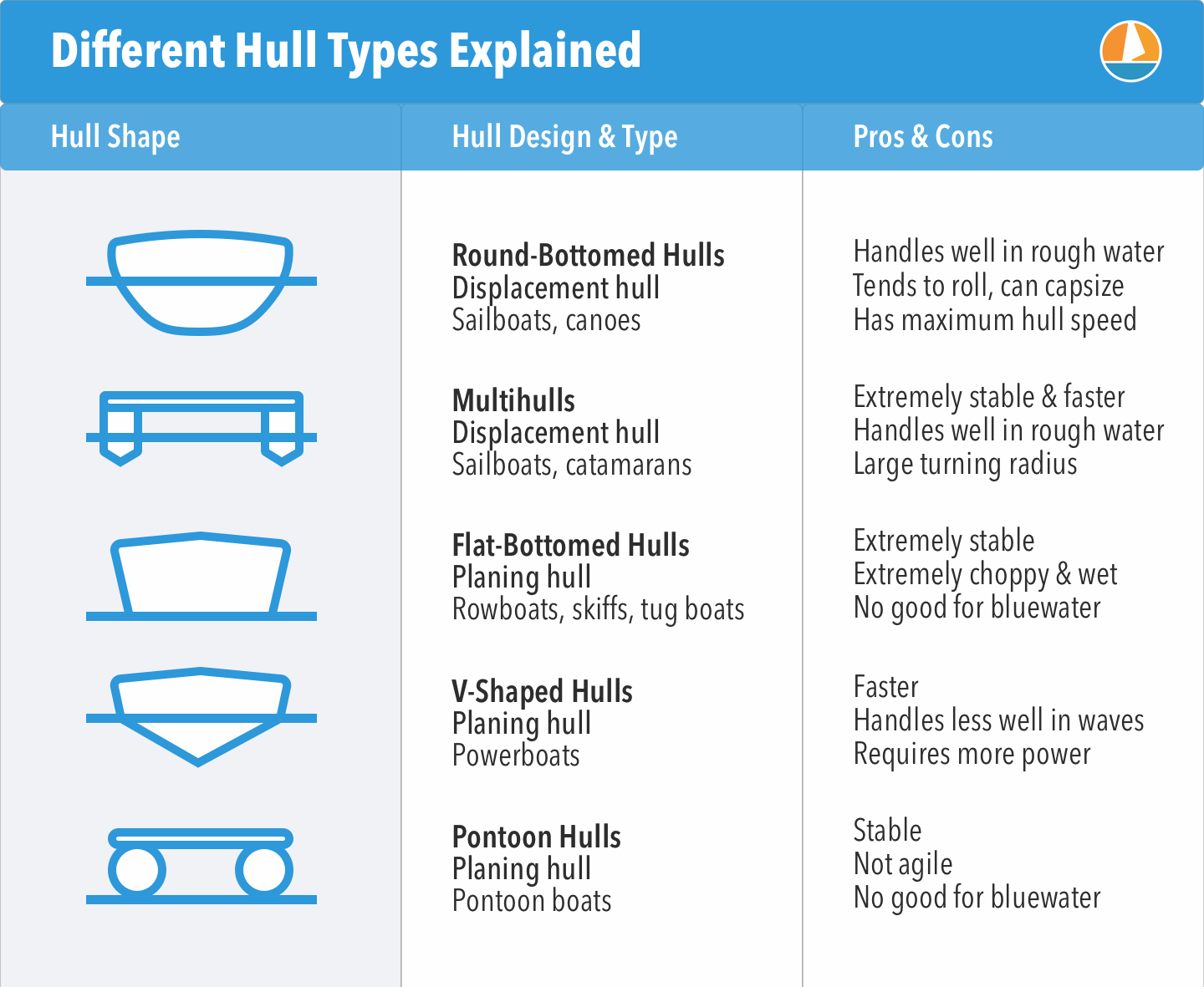

A monohull is a type of sailboat that has a single hull. Monohulls are classified into two categories based on weight and shape: planing and displacement hulls.

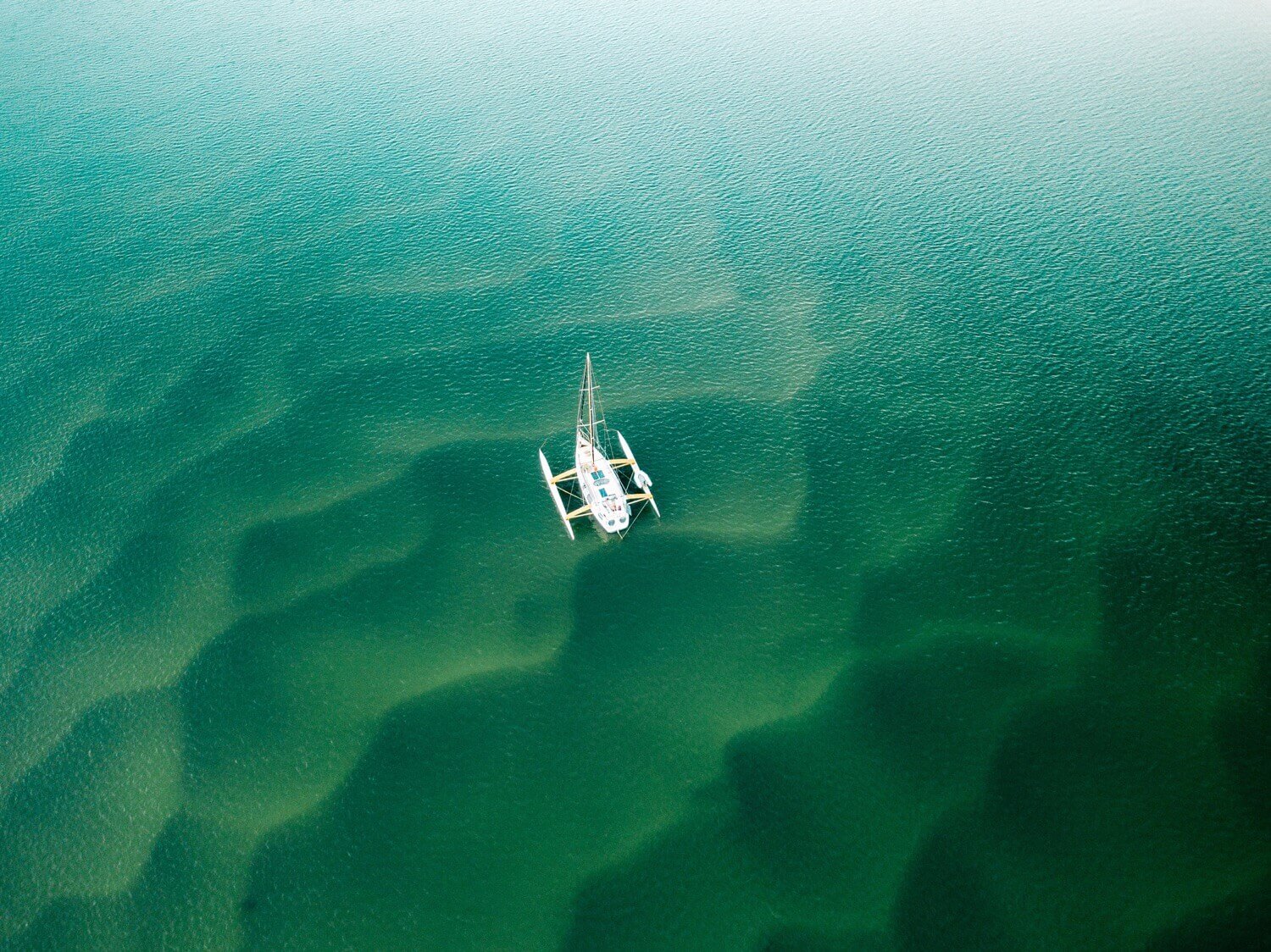

Sailboats with more than one hull are called multihulls. There are two types of multihulls: catamarans, which have two, and trimarans, which have three. These boats are typically designed with planing hulls.

Keel – The fin under the boat

The keel of a sailboat is a structural fin that extends downward from the bottom of the hull. There are several types of keels, each with unique characteristics and advantages. They all serve the same fundamental purpose of stabilizing the boat when we sail by adding lateral resistance in the water and weight at the vessel’s bottom.

Standard keel designs include:

- Lifting Keel

Some sailboats have a retractable centerboard functioning as their keel, allowing them to take the boat into shallower areas.

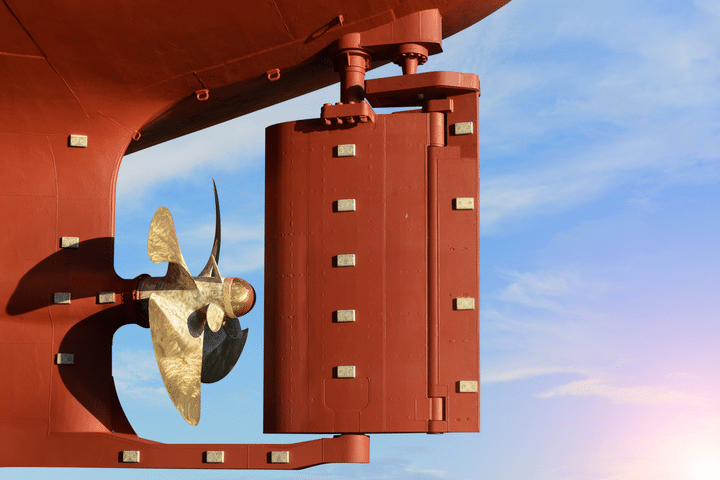

Rudder – To steer the boat

The rudder is a flat surface that sits perpendicular to the waterline. It is connected to the boat by a pivot point, allowing it to swivel left and right. When the steering wheel or tiller is turned, the rudder moves, creating drag in the water causing the boat to turn. The size and shape of the rudder can vary depending on the size and type of boat.

The most commonly seen rudder designs:

- Full skeg-supported

- Semi skeg-supported

Skeg-supported rudders are structurally one of the most reliable and robust constructions, but they are less efficient than a balanced rudder performance-wise. Balanced rudders pivot around their vertical center, giving less drag in the water and higher maneuverability at the cost of being a more vulnerable construction.

Twin rudders are often seen on modern performance sailboats with a wide stern. When the sailboat heel over , the leeward rudder gets better track through the water than a single rudder placed at the vessel’s center line. Contrary to some misconceptions, they can’t be controlled individually, even if the boat has two steering wheels.

Mast and Rigging – Supporting the sails

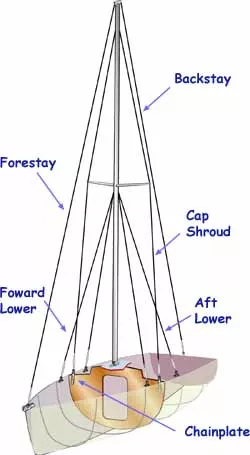

The mast is the long vertical spar that extends upward from the deck of a sailboat and holds the sails. It is the tallest part of the boat and is typically made of wood, aluminum, or carbon fiber. The mast is held in place by stays and shrouds, which form the sailboat’s standing rigging.

Depending on the rig the boat is manufactured with, there are several different types of masts. For example, a sloop-rigged sailboat will have only one main mast, while a ketch-rigged vessel will have a smaller additional mizzen mast placed further aft from the main mast.

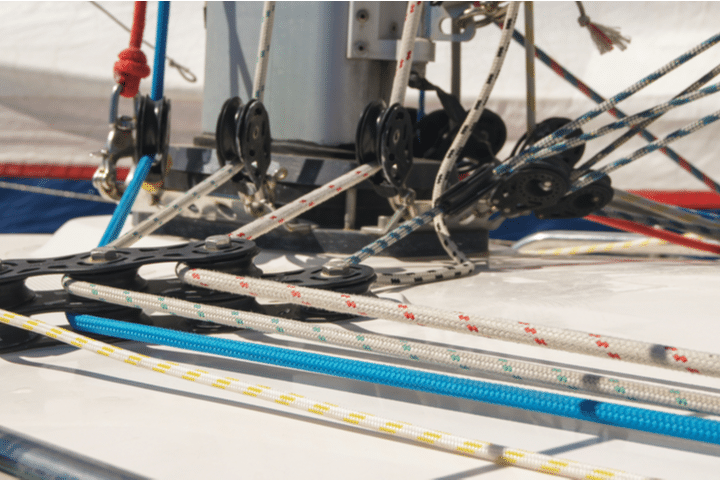

There are two types of rigging:

- The Standing rigging consists of the stays and shrouds that keep the mast or masts in place.

- The Running rigging is the lines we use to hoist, lower, and control the sails.

Pro Tip: “S par” is a general term for a pole made of a solid material like wood, metal, or composite and is used to support a boat’s sail. The mast, boom, spreaders, and poles are defined as spars.

Boom – Supporting the mainsail

The boom is a horizontal beam extending from the mast and supporting the mainsail’s tack and clew (bottom two corners). It is attached to the mast by a hinge called a Gooseneck .

We use the boom to control the shape and angle of the mainsail to optimize its efficiency and power. Some booms also have a Vang or Rod-Kicker installed to assist in trimming the mainsail.

Sails – The canvas used to harness the energy of the wind

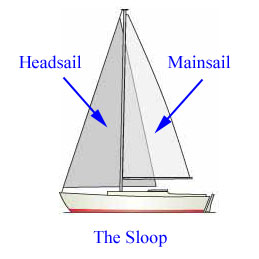

Most vessels have at least two sails, depending on the rig type and boat setup.

The Mainsail flies behind the mast, on top of the boom. Although it may not always be the largest sail on the vessel, we commonly refer to it as “the main.”

The Headsail(s ), located in front of the mast, are often of different sizes and shapes, and many sailboats have more than one. The Jib and Genoa are two of the most common types.

Different types of sails are used for various sail plans and situations, and you can learn more about them in this guide .

Now that we had a look at the main parts of the boat, let us dive deeper and look at the rest of the vessel.

The starboard and port side of the boat

Learning about the boat’s components is very important, but we must also know how to orient ourselves on the vessel. Using the words “left and right” on onboard often leads to confusion.

If you refer to something on the left side of the boat, the person facing you will be confused. He won’t know if you are referring to his or your left. This is where the terms “Port” and “ Starboard ” make better sense.

When facing the front of the boat or the bow , your left side of the boat is the port side, and the right-hand side is the starboard . If you turn around and face the back of the boat or the stern , your right-hand side will be the port side.

- A red light identifies the port side of a vessel.

- A green light identifies the starboard side of a vessel.

Windward and Leeward

- The windward side of the boat is the side facing the wind. If the wind comes from your right-hand side while facing forward, the starboard side is windward. This will be the boat’s high side as the wind heels the boat over.

- The leeward side of the boat is the side opposite to the wind. This will be the lower side of the ship while sailing as the wind heels the boat over.

Windward and leeward are two of the most important aspects to understand when sailing and navigating. Not only to identify equipment and gear on each side of the boat but to avoid collisions when sailing close to other vessels. There are rules on the water dictating which boat is “Stand On” and which has to “Give Way” depending on whether you are the windward or the leeward vessel in the situation.

Read this article to access a free course on navigation rules .

Basic parts of a sailboat

The boat’s bow is the front part, typically shaped like a “V” to cut through the waves. Larger vessels often have a locker for their anchor chain in this section, holding the anchor at the front.

The midship section is the center of the boat. Some refer to this part as amidships.

The stern is the rear or back part of the boat. It is also referred to as the aft . I’ve had French crew calling the stern the butt of the vessel, which is funny but also correct!

The beam is the widest part of the boat. Also referred to as the sides on the middle.

The transom is a flat surface across the stern of the boat.

The waterline is the part where the hull (body) of the boat meets the water. Many vessels have a painted stripe to mark the waterline, indicating how loaded the ship is. If you have too much stuff on board, the waterline goes underwater, and it is time to do some housekeeping!

The freeboard is the vertical part of the ship side between the water and the deck. When you see a blue boat like Ellidah, the freeboard is the blue part.

The deck is the “floor” of the boat when you are outside. You have probably heard the term “All hands on deck!” The front deck is the deck space in front of the mast. Side decks are the decks on the boat’s sides.

The mid-deck is between the cockpit and the mast. The aft deck is the deck behind the cockpit. Sailboats with aft cockpits often don’t have any aft decks, but some have a swimming platform instead.

The cockpit is the boat’s steering position and where you will find the helm.

The helm is the position the helmsman uses to steer the boat. Smaller sailboats often use a tiller to navigate, while most bigger yachts have one or two steering wheels.

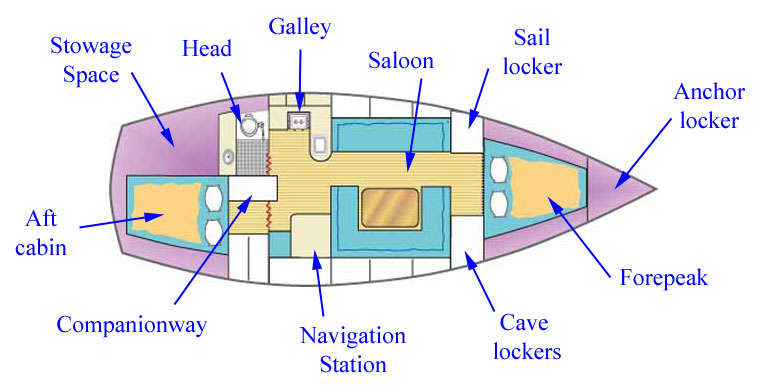

Main parts below deck (inside the boat)

Let us look at the interior to highlight and learn about the parts we have below the deck.

The Companionway

The companionway is the “front door” of the boat. This is where the steps lead from the cockpit or deck down below. It is usually opened and closed using a hatch, two doors, or a plate.

The Galley

The galley is the boat’s kitchen. This is where sailors prepare their delicious meals.

The Saloon

The saloon is basically the boat’s living room, usually where you find the settee and dinette. This is where delicious meals from the galley are served together with refreshing beverages in good company.

The settee is the sofa or couch in a boat. It is also used as a sea berth to sleep in when sailing.

The dinette is the area where you can sit down at a table and eat your dinner. It’s also perfect for consuming rum and a game of cards in good company.

A cabin is often used as a bedroom in a boat but is not necessarily where you sleep. Many boats have more than one cabin.

A berth is a place in the boat where you can sleep. This doesn’t necessarily have to be a bed and can often include the sleeping space in the saloon. Sea-berth usually refers to a sleeping position where you are tucked well in and can sleep when the boat is heeling over and moving around.

The head is the toilet on a boat. If your skipper tells you to go and clean the head, getting out the shampoo won’t do you any good!

Nav station

The navigation station is usually a chart table and a console with mysterious instruments like radios, switchboards, and complicated electronics. This is where adventures are planned and the skipper’s favorite seat onboard.

The bilge is a space in the bottom of the hull where water collects and sometimes a storage space for all sorts of things. It usually contains a bilge pump to pump out water that finds its way into the boat in various places.

A v-berth is a bed in the front cabin shaped like a V.

A bulkhead is a wall inside the boat, usually supporting the structure.

Hardware and Equipment

Sailboats come equipped with a variety of different hardware and equipment. While the specific items may vary from boat to boat, there are some essentials that nearly every sailboat has.

A winch is a metal drum that gives you a mechanical advantage and is used to control and tighten lines. These can be operated by turning a line around it and pulling manually or by a winch handle to get more force.

Most modern winches are so-called “self-tailing,” which means they lock the line on so you can winch the line without holding on to it. Some boats even have electrical winches operated by a button.

A cleat is a fitting used to fasten a rope. Most boats have at least 6 of these. One on each side on the bow, midship and stern. These are used to secure the boat to a mooring buoy or key. Many ships have more cleats than this for various lines and ropes, and they can be used for anything as they are strong points fitted to the hull.

The sprayhood is the boat’s windshield that protects the people in the cockpit from sea spray. Some vessels have a canvas sprayhood that can be folded down or removed. Others have solid sprayhoods, often called a hard dodger or a doghouse .

The bimini is the cockpit’s “roof.” It protects you from the elements and shelters you from spray, rain, and burning sun rays! A bimini can be made of canvas or hard material. A hard bimini can also be called a hardtop .

Dinghy

A dinghy is a little boat you use to get from the mothership to shore when you are at anchor, also called a tender or annex . It can be everything from a small inflatable rubber kayak to a RIB or even a solid boat.

An essential and valuable piece of kit as it is the daily driver for most cruisers. It is like the car of a land crab, used for all commuting on the water and hauling important stuff like beer, rum, and food onboard. Dinghies often have electric or petrol engines, which we call outboards.

Dinghies are also great to use for watersports, such as wakeboarding!

Like Captain Ron said in the movie, fenders are the rubber bumper things you hang off your boat to prevent it from scratching against something like the pontoon or another ship. It is conveniently also used to sit on or as a backrest while relaxing on deck.

A boat hook is a long stick with a hook at the end. Used to grab lines, items, and stuff that is too far to reach by hand, like cushions flying overboard. It is also convenient as a tool to push the boat away from another craft or the key. Most vessels have them on board.

The guard rail can be a flexible wire or a solid metal rail surrounding the boat to prevent us from falling overboard. Some also use a net as an addition for increased safety.

The pushpit is a metal guard rail around the stern of the boat. This is where the guard rail is secured on the stern: a common place to mount the BBQ, life raft, and the outboard for the dinghy.

The pulpit is the metal guardrail on the bow. This is where the guard rail is secured onto the bow.

The stanchions are the metal bars that keep the guard rail in place around the boat between the pushpit and the pulpit.

An arch is a typical structure made of stainless steel on the back of a boat and is often used to mount a variety of items like antennas, radars, solar panels, wind generators, etc. It is also convenient to use for lifting the dinghy and its outboard.

Ground Tackle

The ground tackle consists of several things:

- Your anchor

- Your anchor chain

- The link between the two

- The connection between the chain and your boat

It includes all equipment holding your boat to the ground. Larger boats sometimes have two anchors on the bow.

A windlass is a winch that hoists and lowers the anchor and chain. Most boats have one on the bow and some on the stern. These incredible things can be electrical or manual (some are both) and are essential to anchor your boat when not in a port or marina.

VHF stands for “Very High-Frequency Radio.” It broadcasts on the VHF network and allows you to communicate with others around you. Sadly, you won’t be able to tune in to your favorite radio show on these.

Still, they are essential for contacting other boats and port authorities. It is also the radio you will transmit an emergency mayday over in case of emergency. VHF radios sometimes require a license, depending on the country you are in.

Chartplotter

A Chartplotter is a navigation computer that shows various information on a screen, like charts, routes, radar images, etc. It is another vital piece of equipment that helps you navigate and maneuver the boat.

Final words

I hope this guide has been helpful and not too overwhelming for you. We’ve covered many of the parts of a sailboat and its terms and functions, but this article only touches on the basics. If you want to keep learning about sailing, I have written several other guides to help you get started.

Now that you have a basic understanding of sailboats, it’s time to take the next step and dive into a sailboat’s standing rigging .

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Rigging Small Sailboats - Part 1

Rigging small sailboats.

Part 1 - Rigging in General

Introduction

T his is a basic "how-to" guide for rigging modern single masted sailboats up to about 25' in length. Any person building his own small sailboat, buying a new boat, or one who already owns a boat and wants to replace or change the rig on his boat will find this book valuable. We have attempted to write the book so it can be easily understood by both the beginning sailor as well as the "old salts". However, if you are looking for a "how-to-sail" book, or a book on competition "tuning and racing", or a book on "sailing theory," then this is not the book for you. What is here is practical information on basic rigging and how to install it.

R igging means putting the spars and related equipment in position so the boat is ready for sailing. Rigging also means these items as a functional unit once installed in the boat and made operational. Many terms used herein may sound strange to the beginner and appear to have no relation to the part they describe. Also, many of these terms have no similarity or counterparts to terms used on shore. Nevertheless, they are necessary to the business at hand. Important terms that you should know are initially noted in BOLD type and will be defined where they first appear, as well as in the glossary. Don't try to remember them all once, because after you see them a few times, you'll be able to relate the term to the function, and soon it will become second nature.

T he book is arranged in a logical sequence. PART I concerns mainly the definition and function of the various equipment used in rigging. PART II is the practical "how-to" section on rigging sailboats. All illustrations are noted by a "Figure number", the first number listed referring to the chapter. With the basic information presented, we think you will be able to completely outfit and rig your sailboat with ease and confidence. We have purposely limited the scope of this book so as not to overwhelm the beginner, and yet provide useful information to the large majority of small boat sailors; those who sail the modern rigged boats under 25' in length.

Rigs and Sails

E veryone knows what a sailboat is and most people have heard expressions such as "sloop" or "ketch." These words describe the configuration of the sails and masts on the boat, and we refer to this configuration as the RIG. Rigs have names which are defined by the number of masts the boat has; the number, shape, and locations of the sails; and sometimes by the position of the rigging on the boat. Most small sailboats under 25' have a single mast with one or two sails being used under normal sailing conditions.

T he SLOOP rig has one sail forward of the mast, and one sail aft of the mast. The stoop rig generally comes in one of two variations depending on where the FORESTAY (the wire which supports the mast from the forward side) joins to the mast. A MASTHEAD RIG, such as shown in Fig. 2-1, has the forestay connected to the mast at the very top of the mast (or MASTHEAD). A JIBHEAD RIG, as shown in Fig. 2-2, has the forestay connected to the mast at a point somewhat below the top of the mast. So, when we see a single masted sailboat with a sail fore and aft of the mast and with a forestay that goes to the top of the mast, we call it a "masthead rigged sloop"; and when the forestay is below the masthead, we call it a "jibhead rigged sloop".

A boat with a single mast located well forward in the boat and only one sail, which is aft of the mast, is called a CAT RIG (Fig. 2-3). Do not confuse this term with "catamaran," which is a twin hulled boat, but which may also have a "cat rig." Depending on the design, the mast of a cat rigged boat may or may not be supported with wires (called "stays"; see Chapter 4). Figure 2-4 shows a cat rig with a mast not supported with wires, and is referred to as a "freestanding" or "unstayed" mast.

A nother common rig used in small sailboats is the LATEEN RIG illustrated in Fig. 2-5. This rig uses a single mast, somewhat short, and usually unsupported with wires, onto which is attached two poles. A triangular shaped sail is then attached to these two poles, but not to the mast. The lower pole is sometimes not used, but the rig is still called a "lateen." The rigging of a lateen is usually very simple and uncomplicated.

S ails can be considered the "engine" or power plant of the sailboat, while the rigging can be considered the "transmission," or the means by which the power is transferred to the boat to create motion. Therefore, to understand the rigging, it is necessary to know something about the sail configuration, because both work together as a unit.

J ust about all small sailboat sails are triangular in shape, and the terms used in describing one will generally apply to all. Modern sails are most often made of synthetic fabric, usually polyester (Dacron or equivalent). Some Nylon is used but it is considered inferior because it stretches too much in use, except for special sails such as spinnakers (see following). Sails in the past were made from cotton fabric, and may be to this day, but these require more maintenance and care. The sail of Dacron is virtually maintenance-free; just keep them clean and dry, and check occasionally for damage (see Chapter 11).

S ails have names determined by their function and location on the boat. On boats which have only one sail, this sail is always called the MAINSAIL (the "main" sail on the boat). The lateen rig sail, while still a mainsail, is commonly called a "lateen" sail. Sloop rig sailboats have a mainsail also, and this is the sail located on the aft side of the mast. On sloop rigs, the sail forward of the mast is called the JIB, and the main and jib sail when used in combination for normal sailing are called the WORKING SAILS. The boat in Fig. 2-2 is under sail with main and jib working sails.

S ails other than working sails are sometimes used, especially when racing or cruising. Two of the most popular types are the GENOA jib and the SPINNAKER. The Genoa (commonly called "jenny") is actually just an oversize jib used to increase the sail area, and hence the performance of the boat. The boat in Fig. 2-1 is designed to use a Genoa jib. Sailboats under about 16' long seldom use a Genoa. The spinnaker is a parachute shaped sail (hence the nickname, "chute") used forward of the mast in place of the jib when sailing before or with the wind. Because the spinnaker is considered a "competition" item usually associated with larger boats, and requires specialized gear, it is beyond the scope of this book.

ANATOMY OF SAILS

T he common triangular sail is best discussed by referring to parts OF the sail, and parts IN the sail, or the actual components used in the construction of the sail. Our discussion of sail anatomy is comprehensive, but note that not all sails will have all the items mentioned. Fig. 2-6 should be followed in the discussion of sail parts. Now for the parts OF a sail.

T he LUFF of the sail is the forward part, or the part which is considered to meet the wind first. The LEECH is the aftermost part, while the FOOT is the lower edge of the sail. The HEAD of the sail is the topmost corner; the TACK is the forwardmost corner, and the CLEW is the aft corner of the sail. The ROACH refers to the up and outward curve in the leech of the sail. The amount of roach will vary with the sail. The lateen-type sail has little or no roach, while mainsails used on catamaran sailboats have considerable roach. Next, we will describe the parts built IN a sail.

T o the beginner, the most obvious part built into the sail is the INSIGNIA and sometimes a group of numbers. The insignia usually tells graphically what the name of the boat class is, while the number refers to the registration number given to that particular boat in the class organization. Obviously, not all sailboats belong to a class, nor do they all have numbers on the sails.

M ost mainsails have BATTENS built into them. These are semi-rigid thin strips, either of wood or synthetic material such as fiberglass or plastic, used to maintain the shape of the sail when underway. The battens fit into BATTEN POCKETS sewn into the sail. Battens in order to stay in the pocket can be tied in. A better type uses what is called a "lock-sleeve" pocket which makes it impossible for the batten to slip out, but can readily be removed so the sail can be folded. Battens are usually located at almost right angles to the leech, but sometimes one or two battens are located along the foot at right angles on LOOSE FOOTED mainsails and some jibs. A loose footed sail is one that is attached only at the tack and clew points along the foot. The boats in Figs. 2-2, 2-3, 2-4, and 2-5 all have loose footed mainsails. The position and size of the battens is usually determined by the sailmaker or the designer of the boat. Some sails, especially on certain catamarans, use battens which span clear across the sail.

O ther parts built into the sail are primarily those used to attach the sail to the rigging. At the head, tack, and clew, most sails have CRINGLES built in for attaching the sails. These are merely grommets which reinforce the sail at the hole. Most mainsails have extra sail reinforcing at the head of the sail and this is called the HEADBOARD. The strains on the sail at this point are great, and the headboard with a cringle through it distributes the stresses.

S everal methods are used to attach the sails to the mast, boom, or rigging. The jib and Genoa are attached to the forestay in sloop rigs with HANKS or snaps (Figs. 2-7 and 2-8). These are special hooks or rings used to secure the sails to the forestay as well as allowing them to slide up and down. The hanks are usually sewn into the luff of the sail. Probably the simplest method of attaching the mainsail on lateen rigs, or in boats which have free standing masts, is by means of a "sock" sewn right into the sail which slips onto the spars. Two varieties of sock-type sails are shown by Figs. 2-4 and 2-5. The sock-type sail is limited to very small boats, but makes a neat and inexpensive sail. Also used on small sails are loops or line which fasten around the spars.

O n most boats, the mainsail is attached to the aft side of the mast in usually one of two ways. The first method is with TRACK SLIDES, pieces of hardware sewn to the luff of the sail at intervals of several inches, and which slide on a track fastened to the mast. A better and more common method is the use of a BOLT ROPE. This is a piece of rope the length of the luff and sewn right into it. The bolt rope fits into a groove built into the aft side of the mast. On sails which are not loose footed, this same bolt rope and groove can also be used for attaching the foot to the boom. Or, if track slides have been used on the luff, they too can be used on a track fixed to the boom. For details on spars (mast and boom), see the next chapter.

Masts and Booms

M ost people know a SPAR when they see one, and in sailing, the spars are the "sticks" (mast and boom) to which the sails are attached. To BEND the sails means to attach the sails to the spars and rigging. The MAST is the more-or-less vertical member, while the BOOM is the more-or-less horizontal member attached in some manner to the mast, and usually capable of pivoting about the mast. Most sailboats of the type discussed in this book have one of each. One exception is the lateen rig, which often has two booms, with the upper boom correctly referred to as the "yard" (see Fig. 2-5).

S pars on sailboats are usually made either of wood (solid or hollow), or aluminum (extrusions or tubing, both hollow). It is not uncommon nor undesirable to have an aluminum mast and wood boom in combination. Some typical sections through masts and booms are shown in Figs. 3-1 and 3-2, both for wood and aluminum. Masts made from aluminum should be "anodized"; a special coating process which minimizes oxidization. It is also desirable to wax aluminum masts.

O bserve the methods used for sail attachment. The groove-type mast in either wood or aluminum makes the neatest installation besides being the most efficient. Wood booms are usually solid in the size boats being discussed in this book, due to the small relative size required for the boom. On small sails such as used on lateen rigs, the spars are often nothing more than round wood poles or aluminum tubing.

|

|

T he base of the mast always fits into some type of receptacle or apparatus which is called the MAST STEP. Many types of mast steps are used depending on the configuration desired. Putting the mast in position on the mast step is called STEPPING the mast (see Fig. 9-1). Some masts go through holes in the deck or cabin top and step onto the hull structure, while others bear directly on the deck or cabin top. The simplest type of mast step is the fixed type such as shown by Figs. 3-3 and 3-4. The mast is fixed in position on the step and no movement of the mast is possible, short of removing the mast. Most masts stepped through the deck use fixed steps. Another type is the rotating mast step shown in Fig. 3-5. This type allows the mast to turn or rotate with the direction of the mainsail for greater sail efficiency.

A convenient type of mast step, as far as ease of stepping the mast is concerned, is the pivoting type such as shown in Fig. 3-6. This type allows the mast to be laid into the step fitting, bolted, and pivoted up in position, as opposed to trying to lift it onto the step, which can be tricky, especially on a windy day or if it is a tall mast. With lightweight aluminum spars, it is desirable to use a mast base stiffener at the step when using the pivoting step in order to provide adequate bearing for the pivot bolt.

M any masts require extra reinforcement, and one method of doing this is by utilizing SPREADERS. These are cross members located on the mast at a predetermined location and jutting out sideways. Spreaders are always arranged in pairs, one on each side of the mast. The spreaders "push out" or spread the SHROUDS (the wires supporting the mast from the sides; see Chapter 4) to help stiffen the mast. While spreaders can be made of wood, it is common on small sailboats to have them made of metal tubing, usually stainless steel or aluminum, even when wood masts are used. Some boats do not have any spreaders, while others may have one, two, or more sets. Since spreaders are a necessary evil, (they get in the way and foul things aloft, not to mention added resistance and weight), it is best to have as few as possible.

| FIG. 3-4 This GLEN-L 11 has an adjustable mast step arrangement that allows the boat to be sailed as a cat rig when the mast is moved forward onto the fixed step (to the right), or as a sloop rig when the mast is moved aft along the metal bar base. | |

| FIG. 3-5 A rotating mast step allows the mast to turn with the boom and sail. This type of step can only be used on certain rigs as all the stays must be arranged in a way to permit the mast to turn. |

| FIG. 3-6 A pivoting mast step can be made using aluminum or steel plate or channel. The base has two upright plates welded or formed into a "U"-shape, spaced to match the width of the mast. A slot in each | |

T wo types of spreaders are used. One is the fixed-type where the spreader is rigidly mounted to the mast such as shown in Fig. 3-7. The other type is the pivoting or swinging type which is allowed to swing horizontally along a pivot point located on the mast. This type is illustrated in Fig. 3-8. Use the type specified for the boat you have in any case. Where the shrouds pass over or through the spreaders, there should be special fittings or spreader tips which prevent chafing of the shroud by the spreader. Often the spreader tips are adjustable in order to vary the tension of the shrouds. Most spreader tips have an open groove or hole through which the spreader passes. Note that the shrouds are allowed to move or slide on their own against the spreader tip. However, with the open groove type, some means of lashing or taping the shroud to the spreader tip must be provided. The reason for this is that when sailing at an angle of heel, the WINDWARD* shroud will be taut, and the LEEWARD* shroud becomes slack, which could allow the shroud to fall out of the leeward groove if not secured in place.

*WINDWARD - Toward the direction from which the wind is blowing. *LEEWARD - Downwind, or with the direction of the wind.

T wo other types of spreaders which are used for supplemental strengthening of the mast, or to combat localized stresses, are DIAMOND SPREADERS and JUMPER STRUTS (see Fig. 4-4 'a'). Diamond spreaders are cross members in pairs always used in conjunction with DIAMOND STAYS, which are wire rope stays fixed at either end to the mast. The diamond spreader "spreads out" the diamond stays at their mid-length each side of the mast. The term diamond comes from the fact that when the diamond stays and spreaders are in position, they form a shape like a diamond. An exception to this is when more than one diamond spreader pair is used per stay. Diamond spreaders are just like regular spreaders, except that they are usually smaller and shorter in length.

T he jumper strut is usually used only on jibhead rigs to reinforce the upper part of the mast. The jumper strut is located on the forward side of the mast jutting out horizontally forward, and combats the strain of the mainsail pulling aft on the mast. The JUMPER STAY passes through the strut, and is fastened to the mast at each end of the stay. The jumper strut is usually positioned to bisect the length of the jumper stay. Diamond stays and jumper stays are not required on all boats; just on those masts which require additional support.

T he top of the mast is called the MASTHEAD, and depending on the type of rig, the fittings located here will perform various functions. Masthead fittings will also vary depending on whether a wood or aluminum mast is being used. The masthead fitting for wood masts is usually a custom unit made by the builder (see Fig. 3-9). When building a boat using wood spars, it is usually necessary to fabricate a masthead fitting. The designer should provide details for making the masthead fitting. For aluminum masts, the masthead fitting is usually a ready-made unit or "kit"-type assembly to match the mast extrusion, such as illustrated in Figs. 8-4 and 8-5. Obviously a masthead fitting for a masthead rig will be more complex than for a cat or jibhead rig. In any case, the masthead fitting contains at least one SHEAVE (a grooved wheel or pulley) for the main HALYARD, the line used to hoist the sail. With masthead rigs, the masthead fitting has a sheave for the jib halyard as well, and usually incorporates attachment fittings for the stays, and sometimes for the shrouds also. When a sock-type sail is used, and when the mast has no stays, then no masthead fittings are required. In any case, the top of hollow spars should be capped to keep water out. On wood spars this can be a sheet metal cap, and with aluminum spars, the masthead fitting will usually do the job.

O n boats where the stays and shrouds do not go to the masthead, but fasten to the mast at some lower point as in jibhead rigs, other means are used to secure stays and shrouds to the mast. With wood spars, the conventional method used to attach the shroud and forestay is to use TANGS. Tangs are short metal straps usually with a crimp or bend to splay them out from the mast when in position. Another type does the same job, but these are of cast metal. The strap type usually has at least two holes; one for the stay attachment, and the other for fastening the tang to the mast. When aluminum masts are used, tangs bolted together through the mast can also be used for the shrouds, but the forestay usually uses another fitting called a HOUND (see Figs. 3-10 and 3-11). The hound wraps around the mast for bearing and has a fitting to receive the forestay. If used on a boat with a jib, then a JIB HALYARD BLOCK (fitting with a sheave used to lead the halyard and change its direction) is attached to the hound. If the shrouds and forestay land at the same point on the mast, then the tangs for the shrouds can be integral with the hound fitting.

| FIG. 3-10 & 3-11 A hound strap fitting for use on jibhead rigs with aluminum spars. The hound provides attachment for the forestay as well as a block for the external jib halyard. The main halyard can be run either internally or externally. If run externally, it would run down the forward side of the mast along with the jib halyard (the most common arrangement on small boats). | |

W hen using internal halyards (those which run inside the mast), some type of fitting must be provided for the mast where the halyards exit the mast. Internal halyards can only be used in a hollow mast, and where used, they usually exit at or near the mast base. The simplest fitting is merely a hole through the mast fitted with a FAIRLEAD (a fitting to give a line a "fair lead") to prevent chafing the line (see Fig. 3-12). Another arrangement is to use COAMING PULLEYS or SHEAVE BOXES which not only act as a fairlead, but have sheaves incorporated to change direction of the halyards as well as preventing chafing of the line (see Fig. 3-13). These fittings are usually fitted into the mast near the base. In selecting coaming pulleys and sheave boxes, be sure the sheave of the fitting will protrude far enough into the mast so the halyards will not chafe along the inside mast surface.

T he GOOSENECK is the fitting used to connect the boom to the mast and allow it to move freely, like a universal joint. On the small lateen rig boats the gooseneck is two connected loops which rotate independently (see Fig. 3-14). On conventional rigs, a basic gooseneck is the fixed base type which fastens to the mast. For better sail adjustment, the type of gooseneck which slides on a track or in the mast groove is superior (see Fig. 3-15). Whichever of these types is used, they can be bought as non-swiveling or as a ROLLER REEFING type. The non-swiveling type as shown in Fig. 3-15, does not permit the boom to rotate. The roller reefing type shown in Fig. 3-16, is used so the boom can rotate and allow the sail to be rolled onto the boom in order to reduce sail area when sailing in heavy winds. Goosenecks come in many styles both for wood and aluminum booms with or without the roller reefing feature.

T he CLEW OUTHAUL at the other end of the boom is similar in function to the masthead fitting. It is used to attach the clew of the sail to the boom. Where the mainsail is small, the clew outhaul is sometimes nothing more than a line tied to a cleat. Another method is to use a sheave in the end of the boom in order to gain some leverage so the sail can be pulled taut (see Fig. 3-17). With larger mainsails, the clew outhaul is best a slide fitting located on a length of track, or a type which fits into the boom groove if there is one (see Fig. 3-18). On aluminum booms, and especially when roller reefing is used, a boom outhaul fitting is used which performs the clew outhaul function as well as providing a tang for attaching the hardware used to control the sail .

O ther incidental fittings may often be attached to the spars as well. CLEATS (a fitting used to belay or secure a line, Fig. 3-19) or BOOM BAILS ("U"-shaped straps used to attach blocks to the boom, Fig. 6-2) are commonly used. A BOOM CRUTCH is another item sometimes used, which is not really a part of the boom. The boom crutch holds up the boom when the sails are furled and when hoisting the sail, in order to keep the boom in its proper position.

FIG. 3-19-A CLEAT is a fitting to which a rope may be belayed. This metal cleat is fastened to the side of a mast to belay a halyard, and is a typical example of a cleat.

Click HERE for Part 2

Home > Professional Rescue Boats > Stingray

PROFESSIONAL RESCUE BOATS

Hammerhead Rescue Boat

Stingray Rescue Boat

Manta Ray Rescue Boat

Inflatable Rescue Boat

Rigid Inflatable Rescue Boat

Home > Inflatable Boats > Rigid Inflatable Boats > Rascal

Home > Water Taxi > WT760

Home > Water Taxi > WT1800

Home > Inflatable Boats > Fully Inflatable Boats

Home > Inflatable Boats > Fully Inflatable Boats > Skipper

FEATURED POSTS

We have to moved to a new location in Las Pinas!

HOW TO BUY A WHITEWATER RAFT

Why should I buy an inflatable boat?

Learn How to Sail a Small Sailboat - The Parts of a Sailboat

When you are learning to sail, understanding the parts of a sailboat can be confusing. We have listed the major parts of a sailboat in the diagram below to help get you started.

The common sailboat comprises eight essential parts: hull, tiller, rudder, mainsail, mast, boom, jib and keel. The hull is the shell of the boat, which contains all the internal components. Its symmetrical shape balances the sailboat and reduces drag, or the backward pull caused by friction, as it moves in the water. Inside of the hull in the stern, or back of the boat, is the tiller, which is attached to the rudder in the water. Think of the tiller as the boat's steering wheel and the rudder as the tire. To maneuver a sailboat to the right, for example, you pull the tiller to the right side of the boat, causing the rudder to alter its direction.

If you think of the tiller as the steering wheel, then the sails and the keel are the engines. The mainsail is the larger sail that captures the bulk of the wind power necessary to propel the sailboat. Its vertical side attaches to the mast, a long upright pole, and its horizontal side secures to the boom, a long pole parallel to the deck. Sailors can rotate the boom 360 degrees horizontally from the mast to allow the mainsail to harness as much wind as possible. When they pivot the boom perpendicular to the wind, the mainsail puffs outward. Conversely, it goes slack when swung parallel to the wind. This freedom of movement allows sailors to catch the wind at whatever angle it blows. The jib is the smaller, fixed triangular sail that adds additional power for the mainsail. The keel, a long, slim plank that juts out from the bottom of the hull, provides an underwater balancing force that keeps the boat from tipping over. In smaller sailboats, a centerboard or daggerboard serves the same purpose as the keel, but can be raised or lowered into the water to allow for shallow water sailing.

Before a boat can move in the water, it first must be able to float. In the next section, we'll discover how something as heavy as a sailboat can stay afloat.

Floating depends on two things: displacement and density. Archimedes' principle, which explains the concept of buoyancy, states that in order for an object to float, it must displace an amount of water equal to its weight. As a sailboat's weight pushes downward and displaces water beneath it, an upward force equal to that weight holds the boat up.

Here's where density comes into play. To displace enough water to remain afloat without becoming submerged, a boat must have an average density less than water. For that reason, the hull of the boat is hollow. Whether the boat is made of concrete or fiberglass, its average density is less than water. Think about it: If you put a basketball and a bowling ball in a swimming pool, the air-filled basketball has an average density much less than that of water, so it will float. The solid bowling ball, however, will sink immediately. This is how anything from a small sailboat to an aircraft carrier can manage to stay on top of the water.

Surface area also helps to keep the boat afloat. More surface area gives an object a better chance to displace enough water to offset its own weight. For instance, a small ball of clay likely will sink before it can displace the amount of water equal to its weight. But if you flatten the ball into a thin pancake, there is more surface area to distribute the weight across and displace the water, so it will float. For more information on precisely how a steel ship can float, read how boats made of steel float on water when a bar of steel sinks.

RECENT POSTS

Reminder Regarding Our Authorized Resellers

Enhanced Community Quarantine Announcement

Ang Pagsagwan ni Aljon | Mission Possible

General Notice: Personnel Change

BangkaPro takes part in NDRRMC’s 36 Hour Earthquake Response Simulation Exercise

Successful First Annual Agent/Dealer Seminar and Training

Come Join Us For Our First Annual BangkaPro Seminar!

PVC vs Hypalon Fabric

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

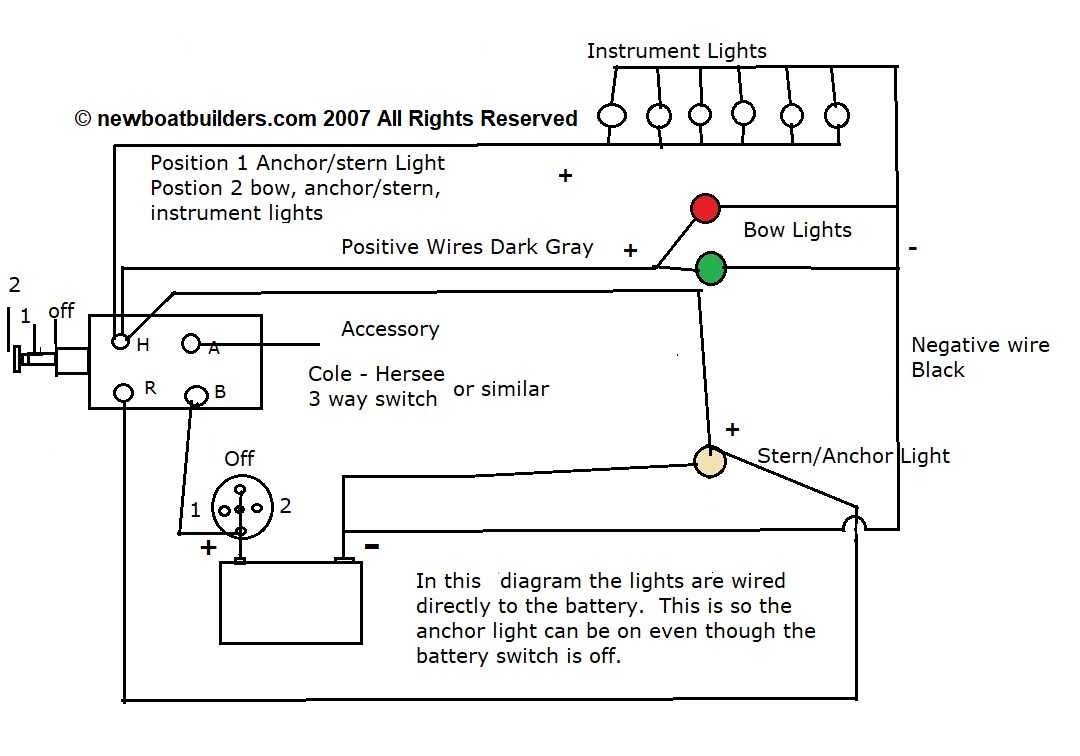

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

The Parts of a Sailboat (of which there are a great many!)

Some parts of a sailboat are very small and cheap, but are far from insignificant. Take the humble clevis pin for example; find one of these on the foredeck and you've cause to be concerned for the security of your rig!

If we were going to discuss all the parts of a sailboat here, it would be a very long article indeed - but relax, that's not going to happen.

Let's make a start with...

The Parts of a Sailboat Above Deck

Dacron is the usual choice of sailcloth for cruisers although laminated sails are becoming more common, and moulded sails are the first choice for racing sailors.

Read more about sails...

The Rigging

The standing rigging , generally made up in 1x19 stainless-steel wire, supports the mast.

The forestay and backstay secure the mast in the fore-and-aft plane, and the shrouds secure it athwartships.

The ends of the stays and shrouds are secured to the structural elements of the hull via chainplates.

The running rigging is the collective name for the lines (halyards, sheets, topping lifts, uphauls, downhauls etc) that control the sails. Their working ends are attached either directly to the sails or, in the case of the headsail, to the boom.

Read more about sailboat rigging...

These are the rigid struts, generally fabricated in alloy, wood or carbon fibre whose job it is to deploy the sails. For example:

- The spinnaker pole;

- The whisker pole;

- The bowsprit;

- The boomkin.

Read more about sailboat masts...

The Cockpit

Like many cruising boats, the Ted Brewer designed Whitby 42 ketch pictured above has a centre-cockpit, which allows for the provision of a sumptuous aft-cabin below. Nevertheless, aft-cockpit boats have a great following with seasoned cruisers too. So what the aft versus centre-cockpit pro's and con's?

Tillers and Wheels

Smaller boats tend to be tiller-steered while larger ones, as in the image above, have wheels. Tillers are attached directly to the rudder stock; wheels are located remotely and operate the tiller through chain or hydraulic linkage.

Each approach has their devotees, but what are the arguments for and against?

The Parts of a Sailboat Below the Waterline

Keels & rudders.

Keels provide three key attributes in varying amounts depending on their design : directional stability, ballast, and lift to windward.

Rudders provide steerage and a small contribution towards lift to windward. They are either:

- Outboard or inboard rudders, which can be

- Unbalanced, balanced or semi-balanced, and be

- Keel-hung, skeg-hung, transom-hung or spade rudders.

Rudder types are discussed here...

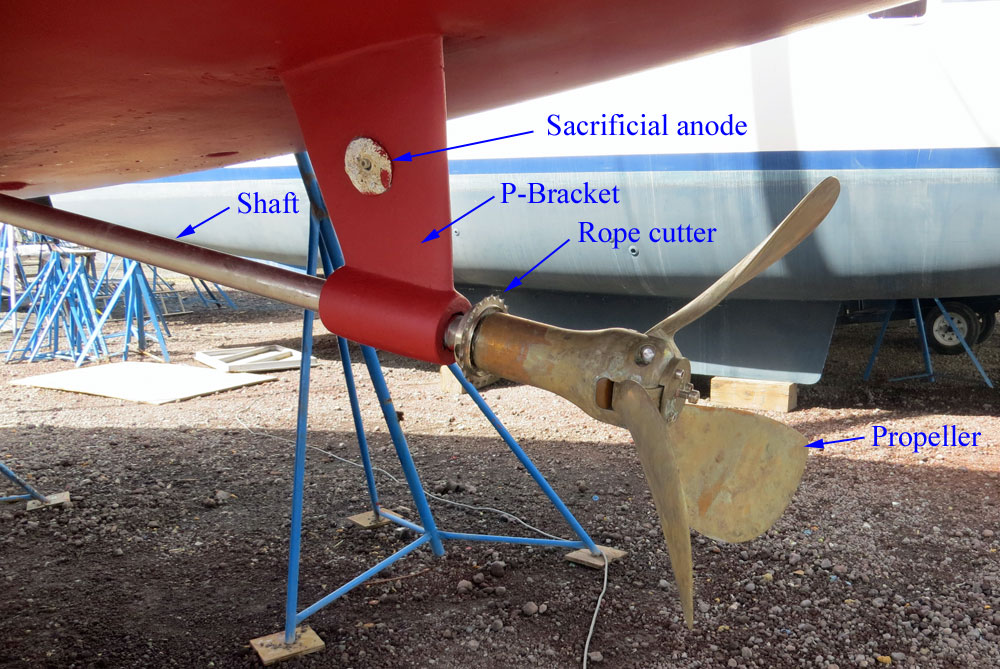

Driven by the boat's diesel engine, the propeller allows good progress to be made when the wind is not cooperating.

Under sail though the propeller is redundant and the fixed blades provide nothing but unwanted drag. This is greatly reduced if the blades can fold aft in a clamshell arrangement or feather in self-alignment with the water flow.

Sailboat propellers are either 2 or 3-bladed - and you can read more about them here...

Below Decks

There's no 'standard' layout for the below-decks accommodation on a sailboat, although the one shown above is a popular choice.

Some layouts work well for offshore sailing whereas others are much less suitable - here's why some succeed where others fail...

Recent Articles

GENERIC KPI Template

Aug 25, 24 07:21 AM

Gulfstar Hirsch 45 Sailboat Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Aug 25, 24 07:19 AM

Nicholson 35 Sailboat Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Aug 24, 24 02:27 PM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

A Guide to the Different Parts of a Sailboat

Table of Contents

Last Updated on November 29, 2023 by Boatsetter Team

When you use Boatsetter, you have the opportunity to choose from a myriad of different sailboat rentals from all over the United States and beyond . A sailboat is a perfect way to relax on the water, either on a solo adventure or on an excursion with friends and family.

When you rent a sailboat with Boatsetter, you will have the option to book a captained sailboat to enjoy your day out on the water or book bareboat to hone your sailing skills. Either way, you may be interested in the intricacies of a sailboat and its different parts. If this sounds like you, you have come to the right place. In this article, we go in-depth about the different parts of a sailboat so that you can be more knowledgeable about whatever boat you may choose and come away from reading this feeling more confident about the whole sailing experience.

A basic sailboat is composed of at least 12 parts: the hull , the keel , the rudder , the mast, the mainsail, the boom, the kicking strap (boom vang), the topping lift, the jib, the spinnaker, the genoa, the backstay, and the forestay. Read all the way through for the definition of each sailboat part and to know how they work.

Explore sailboats for rent near you or wherever you want to go

In short, the hull is the watertight body of the ship or boat. There are different types of hulls that a sailboat may have, and these different hulls will often affect the speed and stability of the boat.

Displacement Hulls

Most sailboats have displacement hulls , like round bottom hulls, which move through the water by pushing water aside and are designed to cut through the water with very little propulsion. The reason these are called displacement hulls is that if you lower the boat into the water, some of the water moves out of the way to adjust for the boat, and if you could weigh the displayed water, you would find that it equals the weight of the boat, and that weight is the boat’s displacement. One thing to know about displacement hulls is that boats with these hulls are usually limited to slower speeds.

Planing Hull

Another type of hull is a planing hull. These hulls are designed to rise and glide on top of the water when enough power is supplied. When there is not enough power behind the boat, these boats often act as displacement hulls, such as when a boat is at rest. However, they climb to the surface of the water as they begin to move faster. Unlike the round bottom displacement hulls, these planing hulls will often have flat or v-shaped bottoms. These are very common with motor-driven water vessels, such as pontoon boats, but they can also be found on smaller sailboats which allow them to glide quickly over the water.

Finally, sailboats can differ depending on the number of hulls that they have. There are three options: monohulls (one hull), catamarans (two hulls), and trimarans (three hulls).

Monohulls , which have only a single hull, will usually be the typical round bottom displacement hull or occasionally the flat bottomed or v-shaped planning hull. Catamarans have two hulls with a deck or a trampoline in between, with the extra hulls providing increased stability. Finally, trimarans have three hulls — a main hull in the middle and two side hulls used for stability. These trimarans have gained popularity because of their excellent stability and ability to go at high speeds.

When evaluating a sailboat , it is important to pay attention to the type of hull that the boat has because the type of hull a sailboat has can drastically change the sailing experience, especially when it comes to stability and speed.

All sailboats have a keel, a flat blade sticking down into the water from the sailboat’s hull bottom. It has several functions: it provides counterbalance, life, controls sideways movement, holds the boat’s ballast , and helps prevent the boat from capsizing. When a boat leans from one side to the other, the keel and its ballast counteract the movement and prevent the boat from completely tipping over.

As with hulls, there are a number of different types of keels, though the two most common types of keels on recreational sailboats are the full keel or the fin keel. A full keel is larger than a fin keel and is much more stable. The full keel is generally half or more of the length of the sailboat. However, it is much slower than the fin keel. A fin keel, which is smaller than the full keel, offers less water resistance and therefore affords higher speeds.

A more recent feature on sailboats is the “winged keel,” which is short and shallow but carries a lot of weight in two “wings” that run sideways from the keel’s main part. Another more recent invention in sailing is the concept of the canting keels, which are designed to move the weight at the bottom of the sailboat to the upwind side. This invention allows the boat to carry more sails.

The Rudder

A rudder is the primary control surface used to steer a sailboat. A rudder is a vertical blade that is either attached to the flat surface of the boat’s stern (the back of the boat) or under the boat. The rudder works by deflecting water flow. When the person steering the boat turns the rudder, the water strikes it with increased force on one side and decreased force on the other, turning the boat in the direction of lower pressure.

On most smaller sailboats, the helmsman — the person steering the boat — uses a “ tiller ” to turn the rudder. The “tiller” is a stick made of wood or some type of metal attached to the top of the rudder. However, larger boats will generally use a wheel to steer the rudder since it provides greater leverage for turning the rudder, necessary for larger boats’ weight and water resistance.

The mast of a sailboat is a tall vertical pole that supports the sails. Larger ships often have multiple masts. The different types of masts are as follows:

(1) The Foremast — This is the first mast near the bow (front) of the boat, and it is the mast that is before the mainmast.

(2) The Mainmast — This is the tallest mast, usually located near the ship’s center.

(3) The Mizzen mast — This is the third mast closest to the stern (back), immediately in the back of the mainmast. It is always shorter than the mainmast and is typically shorter than the foremast.

The Main Sail

The mainsail is the principal sail on a sailboat, and it is set on the backside of the mainmast. It is the main source that propels the boat windward.

A boom is a spar (a pole made of wood or some other type of lightweight metal) along the bottom of a fore-and-aft rigged sail, which greatly improves the control of the angle and the shape of the sail, making it an indispensable tool for the navigation of the boat by controlling the sailes. The boom’s primary action is to keep the foot (bottom) of the sail flatter when the sail angle is away from the centerline of the sailboat.

The Kicking Strap (Boom Vang)

The boom vang is the line or piston system on a sailboat used to exert a downward force on the boom, enabling one to control the sail’s shape. The vang typically runs from the base of the mast to a point about a third of the way out the boom. It holds the boom down, enabling it to flatten the mainsail.

The Topping Lift

The topping lift is a line that is a part of the rigging on a sailboat, which applies an upward force on a spar (a pole) or a boom. Topping lifts are also used to hold a boom up when it’s sail is lowered. This line runs from the free end of the boom forward to the top of the mast. The line may run over a block at the top of the mast and down the deck to allow it to be adjusted.

A jib is a triangular staysail set ahead of the foremost mast of a sailboat. Its tack is fixed to the bowsprit, the bow, or the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two main types of headsails on modern boats.

The Spinnaker

A spinnaker is a type of sail designed specifically for sailing off the wind from a reaching downwind course. The spinnaker fills up with wind and balloons out in front of the sailboat when it is deployed. This maneuver is called “flying.” The spinnaker is constructed of very lightweight material, such a nylon fabric and on many sailing vessels, it is very brightly colored.

Another name for the spinnaker is the “chute” because it often resembles a parachute, both in the material it is constructed from and its appearance when it is full of wind.

People often use the term genoa and jib as if they were the same thing, but there is a marked difference between these two types of sails. A job is no larger than a foretriangle, the triangular area formed by the mast, the deck or bowsprit, and the forestay. On the other hand, a genoa is larger than the jib, with part of the sail going past the mast and overlapping the mainsail. These two sails, however, serve very similar purposes.

The Backstay

The backstay is a standing rigging that runs from the mast to the transom (the vertical section at the back of the boat), counteracting the forestay and the jib. The backstay is an important sail trip, control and directly affects the mainsail’s shape and the headsail.

There are two general categories of backstays:

1) A permanent backstay is attached to the top of the mast and may or may not be readily adjustable.

2) A running backstay is attached about two-thirds up the mast and sometimes at multiple locations along the mast. Most modern sailboats will have a permanent backstay, and some will have permanent backstays combined with a running backstay.

The Forestay

A forestay is a piece of standing rigging that keeps the mast from falling backward. It is attached at the very top of the mast, or at certain points near the top of the mast, with the other end of the forestay being attached to the bow (the front of the boat). Often a sail, such as a jib or a genoa, is attached to the forestay.

A forestay might be made from stainless steel wire, stainless steel rod or carbon rod, or galvanized wire or natural fibers.

Parts of a sail

Sails are vital for sailboats, made up of complex parts that improve performance and maneuverability. In this section, we’ll take a closer look at the different parts of that make up the sails.

Luff – The luff is a vertical sail part that maintains its shape and generates lift by interacting with the wind. It attaches securely with a bolt rope or luff tape for easy hoisting.

Leech – The leech controls air flow and reduces turbulence. Battens or leech lines are used to maintain shape and prevent fluttering.

Foot – The foot of a sail connects the luff and leech at the bottom edge. It helps define the sail’s shape and area. The outhaul is used to adjust its tension and shape.

Head – The sail’s head is where the luff and leech meet. It has a reinforced section for attaching the halyard to raise the sail.

Battens -The b attens are placed horizontally in sail pockets to maintain shape and optimize performance in varying wind conditions. They provide structural support from luff to leech.

Telltales – Sailors use telltales to adjust sail trim and ensure optimal performance.

Clew – The clew is important for shaping the sail and connecting the sheet, which regulates the angle and tension, producing energy. It’s located at the lower back corner of the sail.

Sailing is a favorite pastime for millions of Americans across the country. For some, there is nothing better than gliding across the water propelled by nothing more than the natural force of the wind alone. For both experienced and non-experienced sailors alike, Boatsetter is the perfect place to get your ideal sailboat rental from the mouthwatering Florida keys to the crystal blue waters of the Caribbean .

Smaller sailing boats are perfect for a single day out on the water, either by yourself or with friends and family. In comparison, larger sailing boats and sailing yachts can allow you days of luxury on longer excursions full of adventure and luxury.

Whatever your sailing dreams are, it is always good to know, for both the experienced sailor and the novice, all about the sailboat’s different parts. In this article, we learned all about the boat’s hull, the keel, the rudder, the mast, the mainsail, the boom, the kicking strap (boom vang), the topping lift, the jib, the spinnaker, the genoa, the backstay, and the forestay, which make up the basic parts of any sailboat you might find yourself on.

About us

Boatsetter is the go-to app for boat rentals and on-water experiences. Whatever the adventure, we’ve got a boat for that—Set sail , start the party , go yachting , make your trophy catch , and hone your watersports skills! Download the Boatsetter app ( App Store | Google Play ). Make sure to follow @boatsetter on Instagram, and tag us in all your boat day pictures for the chance to be featured.

Rent. List. Share—Only at Boatsetter

Boatsetter empowers people to explore with confidence by showing them a world of possibility on the water. Rent a boat, list your boat, or become a Boatsetter captain today.

Browse by experience

Explore articles

How to Get More Boatsetter Bookings

Peanut Island Boating Guide

Boating for Beginners: How to Start Boating

The Secret to Happiness? Experience trumps material possession every time!

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Cars & Other Vehicles

How to Sail a Boat

Last Updated: May 13, 2022 Approved

This article was co-authored by Nitzan Levy . Captain Nitzan Levy is a Sailor, Social Entrepreneur, and the Founder of Sailors NYC, a recreational sailors’ club based in Jersey City, New Jersey that specializes in cruising boats and a variety of community programs. Capt. Levy has over 20 years of sailing experience and has sailed in many places around the world including: the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, The Caribbean, and the Indian Ocean. Capt. Levy is a U.S. Coast Guard Licensed Master of vessels up to 50 Tons with Auxiliary Sail and Assistance Towing Endorsements. Capt. Levy is also a NauticEd Level V Captain Rank Chief Instructor, an American National Standards Assessor, an SLC instructor, an ASA (American Sailing Association) Certified Instructor Bareboat Chartering, and an Israeli licensed skipper on Boats for International Voyages. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 25 testimonials and 92% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 976,120 times.

For centuries, the sea has captured the spirits of sailors and adventurers all over the world. In his poem "Sea Fever", John Masefield claimed that all he needed was "a tall ship and a star to steer her by" to feel complete. Breaking into the sailing world can be challenging, but this article will help guide you through the ebb and flood of the nautical world. As a note, this article will help get you started, but it cannot be overstated that before you begin, have an experienced sailor show you the standing and running rigging on your boat and their functions before you venture out on the water on your own.

Gaining a Basic Knowledge of Sailing

- Block: This is the nautical term for a pulley.

- Boom: The horizontal support for the foot of the mainsail which extends aft of the mast. This is what you want to watch out for when changing directions in a sailboat. It can give you quite a wallop on the head if it hits you.

- Bow: This is what the front of the boat is called.

- Centerboard: This is a (usually fiberglass) plate that pivots from the bottom of the keel in some boats and is used to balance the boat when under sail.

- Cleat: Cleats are what lines (or ropes) get fastened to when they need to be kept tight.

- Halyard: Lines that raise or lower the sails. (Along with the sheets, aka running rigging.)

- Hull: The hull is the body of the boat and consists of everything below the deck.

- Jib: This is the sail at the bow of the boat. The jib helps propel the boat forward.

- Genoa: A foresail which is larger than a jib.

- Keel: The keel is what prevents a boat from sliding sideways ("making leeway") in whatever way the wind is blowing and stabilizes the boat.

- Line: Lines are ropes. They are everywhere on boats. There is only one "rope" on a sailboat, the bolt rope which runs along the foot of the mainsail.

- Mainsail: As the name implies, this is the mainsail of the boat. It is the sail attached to the back of the mast.

- Mast: The mast is a large, vertical pole that holds the sails up. Some boats have more than one mast.

- Painter: This is a line positioned at the front of small boats. It is used to tie the boat to a dock or another boat.

- Rudder: The rudder is how the boat is steered. It is movable so that when you turn the wheel or tiller, the rudder directs the boat in the direction you would like the boat to go.

- Sheets: The lines that control the sails. (aka running rigging.)

- Spinnaker: The usually brightly colored sail used when sailing downwind or across the wind.

- Stays and Shrouds: Some wires make sure the mast stays upright, even in very heavy winds. (aka standing rigging.)

- Stern: This is the term for the back of the boat.

- Tiller: The tiller is a stick attached to the rudder and is used to control the rudder.

- Transom: This is what we would call the butt of the boat. It is the back part of the boat that is perpendicular to its centerline.

- Wheel: The wheel works the rudder, steering the boat.

- Winch: Winches help tighten the sheets and halyards. When these lines are wrapped around a winch (in a clockwise direction), a sailor can turn the winch with a winch handle, providing mechanical advantage which makes it easier to bring in the lines.

- Sloop : Sloops are the most common type of sailboat (when you think of a sailboat this is probably the one you picture in your mind.) It has a single mast and is rigged up with a jib in the front and a mainsail attached to the back of the mast. They can range in size and are ideal for sailing upwind.

- Catboat : A Catboat has a mast set up near the front of the boat and is a single-sail boat. They are small (or large, for that matter) and easily operated by one or two people.

- Cutter : Cutters have one mast with two sails in the front and a mainsail on the back of the mast. These boats are meant for small crews or groups of people and can be handled relatively easily.

- Ketch : A Ketch has two masts, with the second mast called the mizzen mast. The mizzen is shorter than the mainmast and is in front of the rudder.

- Yawl : Yawls are similar to ketches with the difference being that their mizzen masts are located behind the rudder. The reason for this placement is that the mizzen on yawls is for keeping balance, rather than for moving the boat forward.

- Schooner : Schooners are large sailboats with two or more masts. The mast in the back of the boat is either taller or equal in height to the mast at the front of the ship. Schooners have been used to commercially fish, transport goods and as warships.

- Port: When you are facing the bow (the front of the boat) the side to your left is the port side.

- Starboard: Starboard is the right side of the boat when facing the bow.

- Windward: As the name might imply, windward is the direction from which the wind is blowing, upwind.

- Leeward: This is also called ‘Lee’. This is the direction to which the wind is blowing, downwind.

- Tacking: Tacking is when you turn the bow of the boat through the wind so that the wind switches from one side of the boat to the other. This is when you most need to be mindful of the boom, as the boom will swing from one side of the boat to the other when you tack (you don’t want to be in its way when it does that.)

- Gybing (Jibing): This is the opposite of tacking, which means that it is when you turn the stern (or back) of the boat through the wind so that wind shifts to the other side of the boat. This is a more dangerous maneuver in a strong breeze than tacking since the boat's sails are always fully powered by the wind, and may react violently to the change in the orientation of the boat to the wind. Care must be exercised to control the boom during this maneuver as serious injury is a possibility if the boom travels across the cockpit uncontrolled.

- Luffing: This is when the sails begin to flap and lose drive caused by steering the boat into wind or easing (loosening) sheets.

Preparing The Boat

- Check the lines ( running rigging ) that raise and control the sails ( halyards and sheets respectively). Make sure that they are separated, not wrapped around each other or fouled on anything else, and that they all have a figure-eight knot or other stopper knot on the free ( bitter ) end so they cannot pull through the mast or sheaves.

- Pull all lines out of their cleats and off their winches. There should be nothing binding any line; all should be free to move and be clear at this point.

- If you have a topping lift—a small line that holds the back of the boom up and out of the way when the sail isn't in use—let it out until the boom sags downward freely, then re-tie or re-cleat it. Watch out for the boom; it's just swinging around at this point; it will cause a painful "clunk" if it happens to hit you or your crew. The boom will return to its normal, horizontal position when you hoist the mainsail completely.

- If so equipped, be sure that the tiller is properly attached to and controls the rudder. Your sailboat is now prepared for you to hoist the sails!

- If your boat doesn't have a windex, tie a couple of nine-inch pieces of old cassette tape, VHS tape, or oiled yarn to the shrouds—the rigging cables that hold up the mast. Place them on each side, about four feet up from the sides of the boat. These will show you from which direction the wind is blowing, although some sailors find cassette tape to be just too sensitive for this purpose.

- If your boat has a motor, use the motor to keep the boat pointed into the wind while you hoist sail.

- Here's a handy tip: if the water is not deep at your dock, or if you have no side pier, walk the boat out away from the dock and anchor it into the sand, and the boat will automatically point itself into the direction of the wind!

Hoisting The Sails

- There will be a small line ( outhaul ) attaching the rear corner of the mainsail ( clew ) to the end of the boom. Pull it so the foot of the main is taut, and cleat. This helps the mainsail have a smooth shape for the air flowing over it.

- Hoist the mainsail by pulling down on its halyard until it stops. It will be flapping around ( luffing ) like crazy, but that's OK for a short period of time. (Excessive luffing will drastically reduce the life and durability of the sail).

- The leading edge of the sail ( luff ) must be tight enough to remove folds, but not so tight as to create vertical creases in the sail.

- There will be a cleat in the vicinity of the halyard where it comes down from the top of the mast. Cleat the halyard. Using the jib halyard, raise the front sail ( jib , genoa or simply the headsail ), and cleat the halyard off. Both sails will be luffing freely now. Sails are always raised mainsail first, then the jib, because it's easier to point the boat into the wind using the main.

- Turn the boat to the left ( port ) or right ( starboard ) so it's about 90 degrees off the wind. This is known as a beam reach .

- Pull on the main sheet ( trimming ) until the sail is around 45 degrees away from straight back ( aft ). This is a safe place for the main while you trim the jib.

- You will start moving and tilting ( heeling ) away from the wind. A heel of more than 20 degrees usually indicates that you're being overpowered. Releasing the mainsheet momentarily ( breaking the main ) will lessen the amount of heel, and you will return to a more comfortable sailing angle of 10 to 15 degrees.

- The jib will form a curve or pocket; trim the sail until the front edge just stops luffing. Keep your hand on the tiller (or helm ) and stay on course!

- If you or the wind hasn't changed direction, this is the most efficient place to set the sails. If anything changes, you have to adjust them in response.

- You have just entered the world of the sailor, and you will have to learn to do many things at once, or suffer the consequences.

Sailing Your Boat

- When the wind is at your back and side ( aft quarter ), it's called a broad reach . This is the most efficient point of sail as both sails are full of wind and pushing the boat at full force.

- When the wind is at your back, you are running with the wind . This is not as efficient as reaching, because air moving over the sail generates lift and more force than just the wind pushing the boat.

- When running with the wind, you can pull the jib over to the other side of the boat where it will fill. This is called wing-on-wing , and you have to maintain a steady hand on the tiller to keep this sail configuration. Some boats have a "whisker pole" which attaches to the front of the mast and the clew of the jib which makes the jib much easier to control and keep full of wind. Be sure to be vigilant of obstacles and other vessels, as having both sails in front of you blocks a significant portion of your view.